no 23. March 2003.

https://www.arts.uwa.edu.au/MotsPluriels/MP2303sm.html

© Sonia Mycak

Sonia Mycak

The University of Sydney

| First published in Karen Herne, Joanne Travaglia and Elizabeth Weiss (ed.), Who do you think you are? : Second generation immigrant women in Australia Broadway, N.S.W : Women's Redress Press, 1992. Reprinted with the author's permission |

To secure our homeland, or to die in battle for it.

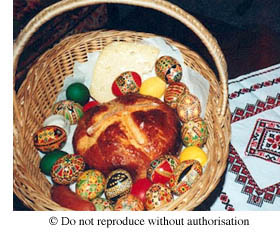

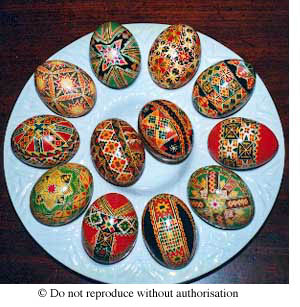

I read the placard at the Ukrainian community centre where I have come for the annual Easter bazaar. Here there are stalls of intricately embroidered blouses and linen, beautifully decorated pysanky, carved woodwork inlaid with coloured paints, plus the usual array of pyrozhky, varenyky, pampushky, holubtsy and the more traditional Easter breads and kolach. The stalls are looked after by faces prominent within the Ukrainian community in Sydney, representatives of various community organisations, and occasionally some of the oldest generation who are still mobile mill around inspecting the Easter fare.

-

Ukraine has not yet died

not its glory

nor its will

fate will smile upon us once more ...

body and soul we will give for our freedom

and show that we are of Cossack heritage[1].

How can I explain to my Anglo-Australian friends the passion of a people torn away from their beloved homeland when it was in the throes of social and political upheaval? How can I explain the nationalistic fervour of a people who have each lost a brother or father in labour camps, who watched family starve to death in the dreaded Stalinist artificial famine of the 1930s, who were chased out of their villages and towns to end up as Displaced Persons in a country with as much spiritual and physical distance from their beloved motherland as Australia?

For many people, thoughts of the 197Os bring back images of flared pants, platform shoes, disco music and the Khemlani loan scandal. For me, it is the time of my childhood, reminiscent of Al Grassby's promotion of multiculturalism, attendance at community festivals such as the Shell National Folkloric Festival, and memories of dancing in the ethnic section at the Easter Show. There was Ukrainian school every Saturday, Ukrainian dancing classes every Tuesday, the Ukrainian scout organisation called Plast, and Ukrainian Church to attend on Sundays.

It's my first day at my new school, and we are lined up outside the gymnasium waiting to go in. This is my first time at a convent school and I'm not used to the hat and gloves and thick stockings which are part of the uniform and set us apart from the kids who go to the local government school.

-

'You can play in the C-grade netball team,' said Sister Ligouri.

'Excuse me Sister, but I can't. I have to go to Ukrainian school on Saturdays...'

'What? uk ... urk ... iranian what???'

'No Sister, Ukrainian ... (by now my voice had become a mere whisper) it's a country near Russia. ... '

'Oh, Russia. Why didn't you say Russia if you mean you're Russian?'

'It's not the same thing ... it's a different language and everything. It's...'

'Yes, well, so you won't be supporting the school ... it figures. I wont see your mother at the Parents and Friends meetings...'

I blushed that lovely shade of crimson which I had developed over the years in response to revelations concerning my other life. A blush which expressed all the pain and embarrassment of living a dual existence in a seemingly singular country. I looked quite normal, I sounded like everyone else, but I had a surname which no-one could ever pronounce, and a grandmother who wore a scarf around her head and flowered ankle-length skirts, who spoke not one word of English, and insisted on coming right up to the gates when she picked me up from school. I remember the tears in my mother's eyes when I asked her to tell Babusia to wait for me around the corner where no-one could see her. The same tears that had met me when six years earlier I had asked to be able to change my name to Margaret or Kerry or Joanne. Of course my parents had tried to make it easier for us. In our family, as in the rest of the community, 'Sviatoslav' had become Edward', 'Volodymyr' had become 'Bob' or Walter', 'Yury' had become 'George' and even 'Stefan' had become 'Steve'. All to make it easier for us.

It's first period, Monday morning. Religion with Sister Margaret Mary.

'Who can tell me what Father O'Malley's sermon was about?'

Her eyes are scanning the room. Somehow I know they will land on me.

'I don't know, Sister,' I reply meekly.

'Didn't you go to Mass on Sunday?'

'Yes, sister. But I went to Ukrainian Church, and we don't really have sermons,

not until the end, and they are about Ukraine.'

Sister Margaret Mary's eyes widen with disbelief. If only I had the nerve to tell her that I had also taken first communion but that it was in our church, and that we also have nuns who are as pious as her except that they teach us in Ukrainian, and that my father had been instrumental in establishing the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Sydney and had been elected to go to Rome as a representative of our community before he died. If only all of that actually mattered, if only all of that could match that look of disbelief on her face.

It's 1954. I haven't been born yet, but my brother is five years old and standing at the gates of the local school, about to embark on his first day there. He speaks no English — at this stage my parents' use of the language is functional but not sophisticated. So, as well as facing the expected trauma of separation from his mother, he is confronting a new culture in a language he cannot speak and can only fleetingly understand. At midday the other children crowd around his lunch box:

'Ugh ... yuk. He's eating a dirty sandwich.'

The young teacher comes over to see why the new boy is crying and the others are laughing at him. She takes one look at his half eaten sandwich, and throws it in the bin.

-

'Come on, we'll get you a nice vegemite sandwich from the canteen.'

She takes his hand and they walk to the next building. She's only trying to be helpful. After all, she's never seen black bread before, and as for that smelly salami — 'well, how is a child meant to eat such spicy food? It's a wonder the child doesn't throw it all up', she says to the ladies putting away the tubs of peanut butter. 'It's no wonder he's such a pale, spineless thing', she says, 'if he has to live on that kind of food.'

-

'Well, they don't know much about nutrition in those countries, do they?'

says one of the ladies by way of explanation.

Of course, no-one told Miss Campbell that she would have a little New Australian' in her class. She's not sure what to do with the wide-eyed fragile looking boy with his funny baggy shorts and unpronounceable name. His eyes plead insecurity; this type of profound fear is something she can't deal with. She's used to kids weeing on the floor and crying for mummy — not this. And somehow he must learn English. It's embarrassing for her, and no good for him, either. So, for his own good, she instigates a system whereby she slaps his wrist good and hard every time he uses one of those foreign words. She even sends him out of the class when he finally starts crying in sheer confusion and utter misery. Eventually his survival instinct takes over, his skin thickens somewhat and his English improves. It improves so much that six years later he becomes dux of the school and wins a place at the selective high school. It improves so much that now, 37 years later, he speaks not one word of Ukrainian.

By the time I was a teenager, a certain conflict of interests was beginning to dominate my life. Allegiance to two cultures was dividing my intellect from my emotions, my days from my nights, my weekends from my weekdays. Two languages meant two names and two signatures; two schools meant two sets of report cards and sports days; two calenders meant two Christmasses and two Easters. Of course this did not always pose a problem. As a child, two sets of Christmas presents seemed a distinct advantage. And the beauty of Ukrainian cultural life was something that every child could adore. Every year I eagerly awaited the time when the women in my family would start baking the rich Easter bread known as paska, in anticipation of the feast which would follow on Easter Sunday. Then the vodka would flow freely and accompany the various zakusky of herrings and horseradish; the roasted meats, cooked to perfection, would lie on the table along with meat and sauerkraut-filled pyrozhky, and the dishes of potato and cheese dumplings known as varenyky would tempt even the youngest of the family. Easter Sunday would be a time of celebration, of merriment and gaiety, where the oldest generation would entertain the youngest, and a time of nostalgia where those old enough to remember would think of those left behind or lost altogether. All this frivolity came after an entire night spent in church, the conclusion of which was the blessing of the Easter baskets, a ritual in which the priest, adorned in an ornate gold and silver gown, would bless the wicker baskets laden with breads and meats and cheeses which each family had brought to symbolise the prosperity of the season of the risen Lord. Nestling amongst the food and the embroidered linen lay the multifarious colours of the pysanky — eggs decorated with wax and dyed in bright colours, adding to the sheer brilliance of the spectacle.

But being Ukrainian was not always so easy. At school, on the television, amongst Australian friends, the assumption was that there was a definable quintessential Australian culture which was at the centre of our lives. And yet for my family, the Ukrainian community was the pivot of our existence. I longed to belong to the first but was inextricably part of the second, and the problem of dual allegiance only increased as I got older.

It's a hot Saturday afternoon in December 1979, and I'm standing on the dry asphalt of a dusty street in Parramatta. We've just finished dancing in the annual multicultural day held in the park near the town hall, and my costume is sticking to my perspiring body as beads of sweat roll down my forehead. Some time has passed, and most of the crowd has dispersed. The stage is empty apart from the odd Macedonian or Latvian kid waiting till their parents have stopped discussing politics so that they can go home and jump into their swimming pool. 'An hour in the car,' I think to myself, 'before I am home in Coogee and can get to the beach.' I, too, am waiting for my mother: she has gone to the nearby shopping centre to pick up supplies from the delicatessens, which always seem to be better around this part of Sydney. I try to undo the top button of my embroidered shirt, but with no luck — it had been sewn on so that it wouldn't come undone whilst we were flying around the stage. My plahta is wrapped tightly around my waist, and the woollen material is starting to irritate my legs which are already weak with heat. More time passes, and after a whole hour has gone by I decide there's nothing to do except go and look for her — maybe the car had broken down or something. As I get to the traffic lights I catch a glimpse of myself in the reflection of a car window, and I suddenly gasp with a slight sense of shock. I've remembered what I'm wearing, and a sense of foreboding overcomes me as I imagine what the trip through the crowded shopping centre will entail. A moment's hesitation — but finally heat exhaustion, irritation and the fear that I'll be left standing here the rest of the day win out over my anxiety. I thicken my skin and prepare myself for the anticipated humiliation so excruciating for a fifteen-year-old.

I step boldly through the doors of Westfield shopping mall, and make a beeline for the first of the delicatessens. My eyes don't leave the ground in front of me, as I imagine every shopping trolley on the entire first floor grinding to a halt as its driver stops to stare at me. Who knows how many people stop to look, maybe hundreds or maybe none. One toddler reaches over to try to touch one of the vermillion ribbons of my headpiece, but I dart quickly to the side. Suddenly as I approach the cut-price butchers, my worst fears are realised and my stomach falls to the ground. There, huddled around a skateboard is a group of boys, some my age, some a little older. They are wearing the heavy metal regalia typical of youth culture in the West, and as they glimpse my braided head-piece, my green velvet bodice, my embroidered underclothes, my bright red boots and my look of sheer humiliation, they begin to roar with laughter. The beads around my neck swing quickly to and fro and the many coloured ribbons fly out around my head as I speed to the door marked 'toilets'. I run to one of the cubicles and lock the door of my haven, as tears of pain and frustration begin to roll down my cheeks.

One of the embarrassing things about my predicament was the fact that no-one ever knew where Ukraine was. My best friend at high school had a mother who was French, and people were positively delighted when they learnt of her background. Assuming that a cultural sophistication accompanied her foreignness, they made polite, almost envious enquiries about the mouth watering crepe suzettes they assumed accompanied her meals at home, told her of their visits to the Eiffel Tower, and spoke of Parisian fashions. No-one poked fun at the baguettes she brought in for lunch. Even the Greek and Italian girls whom everyone knew were 'different' had an identifiable group to belong to, and all the other girls knew where they came from, even if they weren't very impressed.

But for me, in addition to endless justification about my lifestyle, patient endurance of the mispronounciations of my surname and general ignorance of my Anglo-Australian classmates and teachers, there was the ignorance and need for incessant explanation. The simplest approach seemed to be to say that Ukraine bordered Russia and was part of the Soviet Union. However, this meant identifying with a people whom we considered to be economic and cultural oppressors, and it posed certain ideological problems for someone brought up with a strong Ukrainian identity and a nationalistic political agenda in the back of her mind.

It's 1975 and after many months of badgering I've finally been allowed to take part in the pen-friend program being organised at school. My parents never felt that I needed to be involved in any of the extra-curricular activities at my Australian school; in fact, they actively discouraged me from becoming too involved in any of them, especially if they were seen to be promoting friendships with boys. By the time I was a teenager there was much conflict over my desire to be involved in the local Catholic youth group, to attend the school dances to which all my friends went, to wear make-up and dress in ways which were fashionable to all my Anglo friends and acceptable to their parents, but which seemed promiscuous to my family. The answer was always the same: you have your own youth group, your own boys to meet, your own dances, your own school concerts. The problem was they never stopped to define that word 'your' which they used to qualify their argument.

Anyway, it's 1975 and I'm in fifth class, and I'm writing to Glenys Richardson in New Zealand who's going to be my new pen-friend. She's already sent me a letter, my first one ever from overseas, blue with red stripes around the edge, and inside she's put a few of her favourite stickers. She's told me about her life on a sheep station and has promised to send me some nice stamps for my collection, and has even talked about visiting each other when we get to high school! My mother had done everything possible to deflect my interest in the matter, but I remain undeterred, and faithful to the ideals of international friendship and peace which are being propagated in primary schools in the early 1970s. Having pored over my first letter to her for hours, the all-important letter of introduction, I leave it on my desk next to the globe of the world, on which Ukraine has been highlighted with black pen, and go to watch Lost in Space. An hour goes by in which I am so thoroughly engrossed in inter-galactic missions and silver spaceships, that I fail to hear the fuss being made in my bedroom. My brother has barged into my room as usual and has read the letter. He reports to my mother that I don't mention my nationality until halfway through my letter, and worse, that I have called us 'Russians'.

I enter my room to see my mother clutching the crumpled letter to her chest, tears in her eyes, pacing the floor and talking to my grandmother in a shaky voice. She's furious, anyone can see that, but she's also distressed that such a transgression can be made. Why? Why? Why? I overhear snippets of conversation in which my mother is accused of being too lenient and I am labelled as over- indulged and spoilt and far too impressionable for my own good. No-one even hears my quavering voice as I try to justify myself: that just once I didn't want to have to work hard at explaining, just once I wanted to be lazy and make everything fit neatly, just once I wanted to be a little more like everyone else, and not witness the blank stares of incomprehension. How difficult it would be to explain in a letter that I understood Russian because of the success of the 'Russification' the Tsarist and Soviet regimes had undertaken, but that I spoke Ukrainian because we were fighting to preserve our cultural specificity. How difficult it would be to tell people who have no knowledge of complex Slavic history that Ukraine had, over the centuries, been dominated by the Austro-Hungarian, the Russian and the Soviet regimes and that our people have suffered at the hands of all three, but somehow survived with a fighting spirit and dreams of independence. How difficult to explain that all this pain and pride exist in the same little girl who also goes to 'normal' school like everyone else, collects Barbie dolls and stickers and listens to the latest pop music.

It's 1992 now, the little girl has grown up, and the issues are only slightly more resolved. She's less embarrassed now, and values her heritage as a unique part of herself and a bond which extends not only to her own family, but to the Ukrainian community as a whole. But the difficulties are still there, and the complex issue of identity has arisen even more poignantly as recent developments in Eastern Europe and the collapse of the Soviet system have led to changes within the socio-political infrastructure of Ukraine equal only to a revolution: To suddenly be able to communicate with family left long ago but never forgotten; To suddenly be able to travel unrestricted through a homeland known to many of us only through imagination; To suddenly feel the rewards of having struggled to retain cultural specificity in the face of what seemed indomitable pressure to conform. All these involve a new and delicate negotiation of identity in the face of a fierce love for Australia and an appreciation of one's life in and allegiance to the country of one's birth and citizenship. This is the paradox of being second generation Australian and living, as it were, between two cultures. But complexity can enrich as well as confound, and in the world as it exists today no-one is insular. Thus identity is a question for us all, and one which crosses years as easily as it crosses countries.

Notes

[1]The Ukrainian National Anthem

Sonia Mycak is a Research Fellow of the Australian Research Council

(ARC) based in the Department of English at the University of Sydney,

Australia. Sonia's early work was in literary theory and she is author

of In Search of the Split Subject: Psychoanalysis, Phenomenology, and

the Novels of Margaret Atwood (Toronto: ECW Press, 1996).

More recently Sonia's research has focussed upon the multicultural

literatures of Australia and Canada, and culturally diverse writing

communities. She is author of Canuke Literature: Critical Essays on

Canadian Ukrainian Writing (Huntington, NY, USA: Nova History

Publications, 2001) and she edited I'm Ukrainian, Mate! New Australian

Generation of Poets (Kyiv, Ukraine: Alternativy, 2000) and Australian

Mosaic: An Anthology of Multicultural Writing (Sydney: Heinemann,

1997). Sonia is particularly interested in the construction of national

and cultural identities in multicultural societies.

Sonia also works in Canadian studies, focussing on multicultural

literary and cultural studies, ethnic cultural formations and

communities. She is editor of "Australian Canadian Studies", refereed

journal of the Association for Canadian Studies in Australia and New

Zealand. Sonia Mycak is a Research Fellow of the Australian Research Council

(ARC) based in the Department of English at the University of Sydney,

Australia. Sonia's early work was in literary theory and she is author

of In Search of the Split Subject: Psychoanalysis, Phenomenology, and

the Novels of Margaret Atwood (Toronto: ECW Press, 1996).

More recently Sonia's research has focussed upon the multicultural

literatures of Australia and Canada, and culturally diverse writing

communities. She is author of Canuke Literature: Critical Essays on

Canadian Ukrainian Writing (Huntington, NY, USA: Nova History

Publications, 2001) and she edited I'm Ukrainian, Mate! New Australian

Generation of Poets (Kyiv, Ukraine: Alternativy, 2000) and Australian

Mosaic: An Anthology of Multicultural Writing (Sydney: Heinemann,

1997). Sonia is particularly interested in the construction of national

and cultural identities in multicultural societies.

Sonia also works in Canadian studies, focussing on multicultural

literary and cultural studies, ethnic cultural formations and

communities. She is editor of "Australian Canadian Studies", refereed

journal of the Association for Canadian Studies in Australia and New

Zealand. |

Back to [the top of the page] [the contents of this issue of MOTS PLURIELS]