No 18. August 2001.

https://www.arts.uwa.edu.au/MotsPluriels/MP1801oo.html

© Obododimma Oha

Otherness and the rhetoric of the hyperreal

Obododimma Oha

Université Gaston Berger, Saint-Louis / University of Ibadan

The Net, by its very naming, lends itself easily to critical playfulness, which nevertheless represents a serious reading of the nature, processes, and mis/uses[1] of the medium. Polysemous and problematic as a signifier, the word "Net" suggests various attitudes and responses to cyberculture and hyperreality. Examples of wordplay with this term include Gundolf Freyermuth's "The Net Is My Nest", in which the Net is imagined as a city space, a "Personal City" to which people can escape and where they can live comfortably; and Bill Readings' "Caught in the Net: Notes from the Electronic Underground", which discusses the status of scholarly electronic publishing, conceptualizing the Net as a "net" in which the academy is inevitably caught and is being transformed. In fiction about the Net, too, many different approaches are to be found. A recent, striking example is Volker Lehmann's "In the Net", published earlier this year, which tells of two intelligent aquatic beings who are disappointed with the cyberculture of humans (the latter are referred to as "the Others"). Menno, the male character, announces: "This is what they now call reality." However, his partner, Mona, counters with: "I wish they all had these boxes. Then maybe they wouldn't bother us so much." For Mona, cyberculture can be a distraction, as much as it is engaging. Hyperreality tends to seduce people into believing that what is absent is present, into approaching its simulations naively, or, as Porush (1994) writes with reference to Baudrillard, into mistaking "the map for the territory, the model for the thing modeled, the simulation for the original". Being an expression of seductive "'as if' behavior", as Porush identifies it, hyperreality may prevent us from living in the here and now. And since it so enslaves its users, it could, ironically, save the non-humans (from an-Other world) from being "bothered" by human "Others". Yet bothering or troubling Others[2] has been one of the consequences of technology, and is witnessed in cyberculture not only through the frequent creation of textually-transmitted diseases (virus programs), but also through the mis/uses of the Net. Moreover, it is possible that, as John Horvath (2000a) fears, our adventures in electronic technology are disrupting natural processes and silently doing harm to life on Earth. It is thus as if the Net has acquired some powers linked to its literal meaning(s) and, like a fishing net, is catching us unaware.

In Lehmann's fiction, which, interestingly, is about the Net and is published on the Net, one possible meaning suggested by the title, "In the Net ", is that of Mona and Menno not wanting to be caught in the "net" of the Net. To their way of thinking, it is rather better for the human Others to be (caught) in this net they have made for themselves. Yet, being in the Net, on the Net, or about the Net, are all connected issues. Being on the Net (as Lehmann and others are) also means being in the Net, i.e. being trapped. And being on the Net makes a discourse or narrative slippery and so globalized that one cannot master its ramifications. Thus hyperreality includes the Otherness of the cybernarrator and the cybercritic. Indeed, the reconceptualization of the Net as a net implies the presence of Otherness and victimization, and suggests that some agent is using this net against the Other. Nevertheless, a net (as in the case of mosquito net) can also be protective and preservative. The semiotics of the Net thus reveal the different ways we are all held captive, even in the quest for its meaning(s), and for the myriad possibilities it opens up.[3]

In the present article, I examine three types of discourse, an advertisement, some cartoons, and a piece of prose fiction, all of which, through various strategies and devices, rhetorically address the issue of being in the Net. The advertisement, for the Sun Microsystems Dot campaign aimed at convincing businesses to establish an online presence, has appeared in print form in publications such as Newsweek (November 13, 2000), the international news magazine published in New York. With its global coverage and audience, Newsweek is an effective medium for the dissemination of information on business at an international level. Sun Microsystems, Inc., is an international information technology company, with its base in California and branches in over 170 countries.[4] The cartoons, signed by Kiddo,[5] deal with the Net in Africa, and are taken from New People (no.68, September-October 2000), a bimonthly magazine published by the Comboni Missionaries based in Nairobi, Kenya. The prose fiction is Lehmann's already-mentioned "In the Net ", published in the German online cyberculture magazine, Telepolis (18 April 2001).

Clearly, there are great contrasts between these three examples of discourse. While the advertisement may rhetorically "bait" potential consumers with the seductive advantages of hyperreality, the cartoons seek to subvert such rhetoric and subjection of the Other. What is more, the cartoons are from a magazine noted for its critical position on current social and global issues that concern Africa, and seek to present an African perspective on the Net as medium of globalization. Telepolis, on the other hand, is a cutting-edge Western electronic journal, and might be seen to demonstrate the cultural ideology of that "Personal City" (the "polis" in "Tele-polis") imagined by Freyermuth. Such an interpretation is supported by Jay David Bolter's "Electronic Technology and the Metaphor of the City" (1996, also published in Telepolis), in which the onomastics of "tele" and "polis" are analyzed.

In another respect, the short story is interesting because it meets hyperreality at the point of fantasy: both prose fiction and the Net play with reality, the former, in fact, being a more traditional means of creating worlds and transporting us to them, as one may, following Longinus in his theory of sublimity, say. Porush (1994) has drawn attention to the likeness between fiction and hyperreality, noting however that:

-

The difference between the cultural commodity we call "fiction" and the technical-scientific

commodity called "simulation" is the different contracts they sign with their

consumers: a novel always has a disclaimer of reality, tacitly or explicitly;

simulations, by contrast, lay claim to reality, a supposition that is peculiarly

self-reflexive, tautological, tail-biting and yet effective as dissimulation:

a canard, a hoax. Fictions are more honest than simulations.

In narrating on the Net, Lehmann has, interestingly, created a fictional situation in which we, as readers, encounter non-human beings who critique our cyberculture; but the fiction itself is set in the broader context of the simulation of virtual space.

Before going on to discuss the three types of responses to being in the Net, I would like to make an excursus into the domain of existing critical discourse on hyperreality, the powers and mis/uses of the Net, globalization and the implications for Otherness.

| Digital Divide and Other-Worldliness |

The Net is represented in many critiques, especially those from Africa, as a new means of creating and consolidating marginalization, where those without access cannot participate in the "new" world of communication. Olu Oguibe (1999) has drawn attention to the emerging "digital divide". On the one hand, there are those who live and conduct their daily affairs in a new "ethnoscape" or "netscape"; on the other hand, there are those who live in the "meatspace" (Freyermuth, 1998) and are not digitally "connected". The unconnected, as Oguibe makes clear, are not only found in Africa, but also in many technologically advanced countries. The divide means that these people are excluded from "the myriad conversations" that take place in the emergent cyberspace, which is an "enclave of power and privilege"; such an exclusion is fatal because these ongoing conversations do "have significant bearings on or consequences for their condition or wellbeing". Not only can the unconnected Other not respond, but he/she is a victim of the connected and their "exponential craving and readiness to locate and consume the Other in the form of material and visual symbols, without the moral or social responsibilities contingent on a physical encounter with that Other". The unconnected loses voice and presence, as well as the economic rights to his/her own products. Oguibe is thus led to ask:

-

might [the Net] not become a barrier instead of a bridge? Might it not preclude

proper and meaningful contact and exchange, by encouraging the false notion

that we know the Other and that the Other is in fact part of the new global

community that we take for granted? Might it not impede rather than facilitate

our reach for genuine interaction across social and cultural divides by creating

simulacral rather than real contact and exchange? Somehow, one wonders: in

the end, might the Net not come between us and the Other we do not know?

Yet, in spite of his skepticism about the ability of the Net to facilitate cross-cultural conversations, Oguibe recognizes the fact that it is a vital tool for development in the modern world. His worry is about its misuse by those who are privileged to have it (see also Oguibe 1996).

Ami Isseroff (1999), responding to Oguibe, quite rightly points out that it is better to be badly connected than not to be connected at all. Being badly connected calls for an improvement in an already-existing system, while being unconnected means being a total stranger to this form of information technology. Interestingly, too, "unconnected" is an ambiguous expression, because it may suggest a lack of concern. In this case, the problem of being unconnected is plural because those who are not connected to the Internet may possibly feel that they want nothing to do with this new form of communication, whereas in fact it will impact on their lives, whether they use it or not. Knowing that one is caught in the Net and seeking to understand it is one thing; a total unawareness that one is caught in the Net is another. Thinking that one has no business with the Net is in itself a barrier - one which cannot be blamed on those we accuse of using this new technology to dominate or divide the world.

John Horvath (2000b) draws our attention to the fact that the digital divide predates the Net, and is related to much broader factors:

-

it is clear that the "digital divide" has little to do with computers and

Internet access. This doesn't mean it's non-existent. It does exist, and has

existed for thousands of years: it's traditionally known as poverty, social

exclusion, racism, and sexual discrimination. Thus, computers and the Internet

have not created a new social ill, but have exacerbated existing ones. Any

solution aimed at dealing with this problem, therefore, must first take into

consideration its underlying causes - causes which are deeply rooted in basic

social, political, and economic aspects.

The Net, however, does create opportunities for the Other. For example, Misty Bastian (1999) refers to the use of the Net by some emigrant Nigerians to pursue questions of national identity, to promote politically engaged discussions of their homeland, and even to become politically active. Although we must not forget that cyberpolitics and "electronic democracy" may be misleading and even counterproductive (Schuler 1999), the Net, nevertheless, creates an arena where the Other can seek to establish a deconstructive presence, turning the Master's tools to his/her own needs. In relation to Africa, those tools may serve as the material means of answering back, but they must be made use of, as Stephen Mbogo (2000) warns:

-

Critics of cultural imperialism will point out that the Internet is heavily

dominated by the West, particularly the USA, and is essentially a medium for

the propagation of Western culture and ideas. The challenge facing Africa

is to project and promote her cultures in this marketplace of civilizations.

This is the only way for her people to avoid being just consumers of other

people's cultures. A radical change in mentality is needed, lest the development

of these information technologies may turn out to be another instrument to

perpetuate the domination of the North over the rest of the world. (22)

If the Net can promote Western culture and ideas, it can do the same for other cultures and ideas. It is time for Africans to take over their own economic and artistic resources, rather than leaving them to be exploited by others in cyberspace. It is reassuring that many African artists like Oguibe have homepages, which they use to promote their work. Oguibe's website, as we are informed on the top page, has been acclaimed as a World Wide Web Associates top-ten site of African-American art. Virtual culture can be exploited successfully by artists and others of African origin, allowing them to belong to, and benefit from, the Information Age.

Mbogo, just like Oguibe, identifies some obstacles to Internet connectivity in Africa, such as illiteracy, lack of telephone access, insufficiency of bandwidth, high cost of Internet access, etc. As we will see below, these problems also inform Kiddo's cartoons of the Internet in Africa. Moreover, they further confirm what Horvath and others have said about the digital divide predating the Net, and simultaneously indicate areas which, with the emergence of the Net, require urgent attention.

In not taking advantage of the Net, Africans (and those assigned to the "Other-worldliness" of the "meatspace") will be further marginalizing themselves. Participation in the virtual world offers Africa the opportunity of challenging aspects of Net culture imposed by the West; for instance, the spreading authority of Western tongues (especially English) as the languages of the Net. Computers can also communicate in African languages if they are programmed to do so. The voices of the (African) Others need to be heard on the Net - even if the (African) Other is simultaneously caught in the Net.

| Rhetoric, NEToric, and Real Transactions |

Advertisements of Internet services construct a NEToric, by which is meant a rhetoric that portrays the Net as a kind of God we can fail to worship only at our peril. Exaggeration, of course, is a strategy often used in the advertisement of goods and services; and such NETorical advertisements notoriously exaggerate and even mythologize the powers of the Net. A classic example of this is the Sun Microsystems Dot advertisement.

Like God, the Internet emerges in the advertisement as invincible and omnipresent: "THE DOT", as in dot-com, is, we are told, "THE MOST POWERFUL FORCE IN THE UNIVERSE", and its power "IS EVERYWHERE AND IT'S ALWAYS ON". With the Internet, which possesses these extraordinary qualities, a businessperson becomes a serious threat to anyone foolish enough to engage in competition: "WITH THE DOT IN .COM YOU KNOW NO BOUNDARIES, AND YOUR COMPETITION KNOWS NEVER TO ENTER YOUR WATERS". Why not? Here the language ("FEROCIOUS INTERNET COMPUTING TOOLS") and visual imagery (a lone swimmer on the surface of the ocean, oblivious to the dot speeding upwards from the depths below) converge in the recreation of a metaphorical context inspired by the Jaws movies and advertising posters (see a summary). In place of the shark, the dot. In place of the female swimmer in a swimming costume, a man in a business suit. Like the great white shark which posed such a terrible threat to swimmers in Stephen Spielberg's original 1975 Jaws and subsequent follow-ups, the advertisement is suggesting that the dot will catch unawares and destroy any unwary competitor without an Internet presence who strays into these waters.

In the film, a marine biologist explains to the mayor that the shark is very much like a machine - the killing machine of the popular parlance:

-

Mr. Vaughn, what we are dealing with here is a perfect machine - uh, an eating

machine. It's really a miracle of evolution. All this machine does is swim

and eat and make little sharks, and that's all.

There is an ironic crossover of meaning in the advertisement's appropriation of an animal, which is often described as a machine, to indicate the ferocity of a system, the Net or Web, which depends for its very existence on a network of machines around the world.

The Net can be a great asset to a business enterprise, enabling fast and efficient transactions in international markets. However, in spite of the Net's ability to break down certain barriers of geography and distance, to claim that a business with the Net will "KNOW NO BOUNDARIES" is little more than hype, a vast overstatement. Curiously, this is one of several places where the metaphorical context breaks down and almost self-de(con)structs. In Jaws, the shark not only attempts to protect its domain, but also recognizes no boundaries, effectively extending its domain well beyond its usual limits. The ability proclaimed by the Dot advertisement to violate boundaries and claim every location as the space of the Self is problematic: what happens when the Other has the dot too? Shark against shark? Dot against dot? Who then controls what part of the water? Is the dot a deterrent to potential competitors, who will shy away from entering these waters? And yet, was the great white shark not eventually destroyed, precisely because it recognized no boundaries, and in spite of its ferocity? Indeed, is there not a great irony in that the advertisers are using a very negative image, that of the fearsome shark, and suggesting that businesspeople should operate like that shark - feared and loathed by nearly everyone, and eventually eliminated?

The hyperbolic description of the dot as "THE MOST POWERFUL FORCE" and "FEROCIOUS", along with an odd mixture of other images such as "ULTRA AVAILABLE" and "IRONCLAD STORAGE", the latter being more suggestive of a cage to protect against a shark than of the shark itself, is reinforced by the capitalization of the entire text, with extra-large type reserved for the most evocative words and phrases. The advertised item is supposed to appear irresistible and indispensable. Ultimately, the hype is different only in degree from the self-introduction, which is also an advertisement, found on Sun Microsystems' website. Again, it is a NETorical trap for the business entrepreneur who dreams of making it big:

-

What we're seeing right now is a convergence of exponentials. Exponential

increases in processor speed. Exponential increases in bandwidth. Exponential

increases in the number of users, devices, and data types linking to the Internet.

Call it the Net Effect. It all adds up to two things: incredible new opportunities

and equally incredible challenges. Helping you get ready for them is what

Sun does best. Our hardware and software products are designed to scale to

the nth degree, so that you're always nth ready.

In summary, then, it can be said that the Sun Microsystems Dot advertisement represents a Western techno-commercial perspective on "e-life" in the new business community. Sea imagery has often been appropriated to describe our interaction with the Net - "surfing the Net" is a commonplace phrase - but the advertisement warns against free and easy attitudes, reminding us of the dangers that lurk beneath the surface of the water, especially for those who are unaware of the power of the dot which may be adopted by their competition. At the same time, the advertisement turns ancient terror, as distilled in the modern Jaws films, on its head, making it appear desirable - or at the very least necessary if you want to survive in e-business.

The Sun Microsystems advertisement is a good example of a widespread contemporary trend, that of mythologizing technology and portraying it as omnipresent and omnipotent. The NEToric of the advertisement therefore sets a trap, or rather casts a net, in the hope of catching some big business fish. Schuler (1999) writes of the Techno-Utopian vision of:

-

a new world created for the entrepreneurs, eager trend-surfers who ride

the wave nanoseconds before the rest of the pack, deftly slipping onto the

next one while the previous one crashes apart. Right now, the wave is unmistakably

electronic: go, [sic] cyber, young entrepreneur!

Yet it is not only (business) entrepreneurs who may be caught in this net. The Internet, suggests Sun Microsystems, is a means of turning "INFORMATION INTO POWER". Information and power are all very well, of course, but what of physical needs such as food, shelter and health facilities? At this point, let us turn to the cartoonist Kiddo.

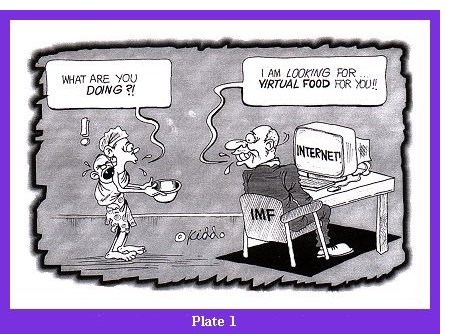

In Plate 1, Kiddo

can be seen to be satirizing the International Monetary Fund (IMF), portrayed

here as an organization that pursues the illusory hope of solving problems

of poverty and hunger through the Net. Recent demonstrations and agitations

against the World Bank and IMF provide a background to this image. The Internet

might be said to symbolize the fallacious belief that globalization will solve

everyone's problems. The IMF's hunger for "virtual food" has little in common

with the hunger of the woman and her baby for physical food. This is a clash

of discourses, of two different forms of rhetoric, generated by the

polysemy of the word "food" (and the implied concept of "hunger"). On the

one hand, we have the rhetoric of hyperreality - the NEToric - which

is characterized by a semiotics of simulation, in which information becomes

"food", because it satisfies hunger for knowledge. On the other hand, in a

real-world context, physical needs require physical solutions. The woman's

startled question locates her firmly in a world where "doing" has a very different

meaning than for the representative of the IMF. This draws attention to another

kind of "digital divide" - one located in discourse, or between different

forms of discourse, and where those whose existence is circumscribed by the

real world are semiotically alienated from those who also participate in the

cyberuniverse. Not only does the woman not possess a connection to the Net,

neither does she possess the language of the cyberworld. The Net, as a communication

medium of globalization, fails to unify the world; instead it creates different

worlds of discourse, which consolidate exclusion.

In Plate 1, Kiddo

can be seen to be satirizing the International Monetary Fund (IMF), portrayed

here as an organization that pursues the illusory hope of solving problems

of poverty and hunger through the Net. Recent demonstrations and agitations

against the World Bank and IMF provide a background to this image. The Internet

might be said to symbolize the fallacious belief that globalization will solve

everyone's problems. The IMF's hunger for "virtual food" has little in common

with the hunger of the woman and her baby for physical food. This is a clash

of discourses, of two different forms of rhetoric, generated by the

polysemy of the word "food" (and the implied concept of "hunger"). On the

one hand, we have the rhetoric of hyperreality - the NEToric - which

is characterized by a semiotics of simulation, in which information becomes

"food", because it satisfies hunger for knowledge. On the other hand, in a

real-world context, physical needs require physical solutions. The woman's

startled question locates her firmly in a world where "doing" has a very different

meaning than for the representative of the IMF. This draws attention to another

kind of "digital divide" - one located in discourse, or between different

forms of discourse, and where those whose existence is circumscribed by the

real world are semiotically alienated from those who also participate in the

cyberuniverse. Not only does the woman not possess a connection to the Net,

neither does she possess the language of the cyberworld. The Net, as a communication

medium of globalization, fails to unify the world; instead it creates different

worlds of discourse, which consolidate exclusion.

Cartoons, like advertisements, also exaggerate in trying to satirize and evoke humor. Tejumola Olaniyan (2000) has rightly observed that:

-

Embodied in cartooning is simultaneously a prescriptive and proscriptive

challenge in which to be more iconic, i.e. "realistic," is to lose its cartoonish,

i.e. caricaturist, essence, while to turn the other way round and be less

iconic, i.e. "abstract," is to lose its referential power and thus its audience

and function.

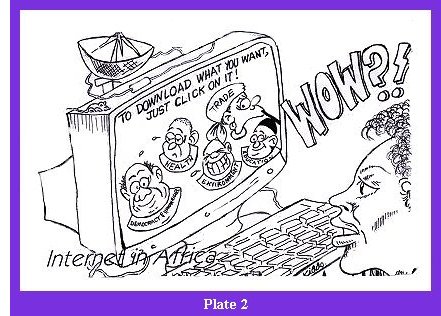

The tendency in Kiddo's cartoons is to be less realistic so as to achieve greater caricature of the Internet and its presence in Africa. This is seen again in Plate 2.

Here,

the hyped capacities of the Net are ridiculed. The legend on the computer

screen reads: "To download what you want, just click on it!", as if we were

in a kind of Aladdin's cave. The options are Democracy and Human Rights; Health;

Environment; Trade; and Education. The icons representing these options, ironically,

speak of undesirability; the icon for Health, for example, is a sickly face

with a head that is either balding or shaved. The face of Democracy, meanwhile,

is that of an aging man, which suggests that he is out of fashion or out of

touch, and may remind us of the sham democracies of certain African rulers

who maintain themselves in office, once in a while organizing phony elections

and reinstating themselves in positions of power. The baldness of the Environment

icon is significant because it clearly relates to the ruined and bare environment

that has emerged from the misuse of technology and mindless exploitation of

natural resources. The closed eyes may symbolize a lack of vision, in which

case the laughter could indicate contentedness with this lack. All in all,

this image hints at the untroubled consciences of the globalizers in respect

of environmental degradation. Such visual icons, then, help to deconstruct

the magic promises made in the discourses of/about the Net.

Here,

the hyped capacities of the Net are ridiculed. The legend on the computer

screen reads: "To download what you want, just click on it!", as if we were

in a kind of Aladdin's cave. The options are Democracy and Human Rights; Health;

Environment; Trade; and Education. The icons representing these options, ironically,

speak of undesirability; the icon for Health, for example, is a sickly face

with a head that is either balding or shaved. The face of Democracy, meanwhile,

is that of an aging man, which suggests that he is out of fashion or out of

touch, and may remind us of the sham democracies of certain African rulers

who maintain themselves in office, once in a while organizing phony elections

and reinstating themselves in positions of power. The baldness of the Environment

icon is significant because it clearly relates to the ruined and bare environment

that has emerged from the misuse of technology and mindless exploitation of

natural resources. The closed eyes may symbolize a lack of vision, in which

case the laughter could indicate contentedness with this lack. All in all,

this image hints at the untroubled consciences of the globalizers in respect

of environmental degradation. Such visual icons, then, help to deconstruct

the magic promises made in the discourses of/about the Net.

The poverty of Net discourse - or the poverty facilitated by the Net - is

further intimated through the presence, atop the monitor, of an actual mouse,

which serves as a literal representation of the "mouse" used in operating

the computer. Mice are not only a traditional symbol of poverty, as in the

English phrase "as poor as a church mouse", but their near-relatives, rats,

have multifarious negative associations, suggesting at the very least a badly-kept

environment, but often functioning as symbols of decay. If it is possible

to download whatever benefit is required from the Net, then why is this ambiguously

signifying creature crouching on the monitor? In the final analysis we must

concur with Mbogo (2000) that:

"The starving children of Africa cannot eat e-mails; computers do not produce food or clothes, nor dig water wells; Internet connections will not pay for aspirins and syringes." (13)

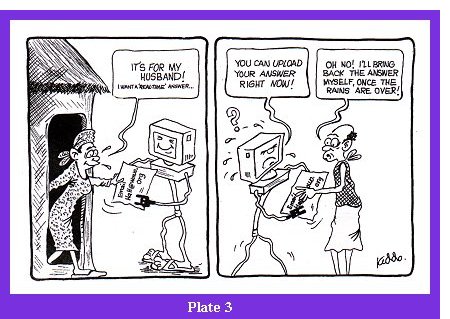

As illustrated in Plate 3, the Internet is not always a suitable medium even for the simplest of messages, which may entail requirements that cannot be electronically satisfied. Here, a woman emails her husband, actually handing over a written piece of paper to the embodied Internet, whose head is a computer monitor. That she seeks to use the Net like a human messenger is made clear by this interaction; she is not really part of the virtual conversational sphere enabled by the Net, nor does she wish to be. Indeed, she explicitly states that she wants a "'real-time' answer". When, in language typical of the cybersphere, of NEToric, the Net messenger advises her husband to "upload" his response to his wife "right now", the man is wise enough to opt out of this discourse (assuming he is even capable of participating in it!) and says: "Oh no! I'll bring back the answer myself, once the rains are over!" He would rather wait to give an answer - and knows his wife would rather wait to receive an answer - in accordance with the natural rhythms and cycles of the real world.

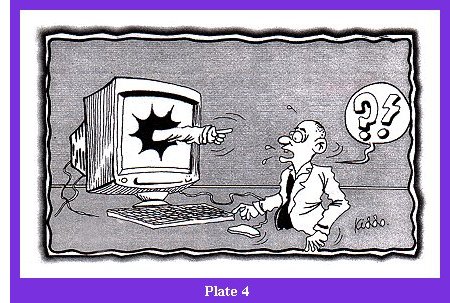

Plate

4 contains no text, merely the question mark and exclamation mark symbols

which reflect the speechlessness of a man confronted by a hand which has burst

through the computer screen and is pointing directly at him. We cannot help

but be reminded of the monster and the fate of the scientist in Mary Wollstonecraft

Shelley's Frankenstein. Pushing science and technology to extremes,

especially where these run counter to the natural cycles mentioned above,

may spell disaster. What kind of monsters might we be unleashing on the world?

Are the (hidden) costs of technology too high? (see Horvath 2000a).

Plate

4 contains no text, merely the question mark and exclamation mark symbols

which reflect the speechlessness of a man confronted by a hand which has burst

through the computer screen and is pointing directly at him. We cannot help

but be reminded of the monster and the fate of the scientist in Mary Wollstonecraft

Shelley's Frankenstein. Pushing science and technology to extremes,

especially where these run counter to the natural cycles mentioned above,

may spell disaster. What kind of monsters might we be unleashing on the world?

Are the (hidden) costs of technology too high? (see Horvath 2000a).

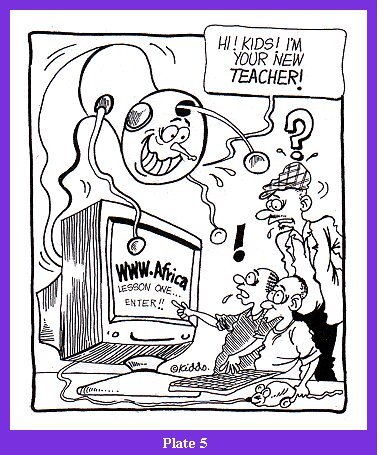

The Net is a useful means of pursuing formal and non-formal education, but cannot completely replace a human teacher and a classroom context. The classroom experience of pupils is part of an essential process of learning to live, work and achieve together, with the human teacher playing a significant role. The cartoon in Plate 5 addresses this subject, demonstrating the horror of both students and a teacher at the idea that the Net is taking over education. Of course, to begin with, using the Net itself requires specialized technical training; and for such a form of education to succeed in the African context, it has to be available in language and semiotic forms comprehensible to the majority of Africans. The use of very technical, foreign language in Net education leads rather to a politics of exclusion (Mbogo, 2000: 20).[6] The linguistic/semiotic barrier recalls Basil Bernstein's (1975) deficit hypothesis, which suggests that children from a lower socioeconomic class are disadvantaged at school, where an "elaborated code", with which they are not familiar, becomes the norm. Africa's children would obviously face this problem in the use of the Internet as their "new" teacher. Furthermore, as in Plate 3, the computer "mouse" is literally presented by the cartoonist so as to evoke humor but also to convey a critical message about the poverty of (African) cybereducation. In summary, it can be seen that Kiddo's cartoons make judicious comments about the intrusion of the Net into the lives of ordinary Africans. In a sense, the cartoons show the Otherness of these Africans in relation to cyberculture.

But when we turn to Volker Lehmann's short story "In the Net", we find that Net also marks out the Otherness of human beings generally. Living in a natural state, the non-human protagonists, Mona and Menno, mermaid-like aquatic beings, find the ways of humans ("the Others") strange. The unreality of human lives is underlined in the passage where Mona and Menno stumble across cyberporn on an abandoned computer:

-

Mona continued hitting buttons, but after a while became bored. No matter

what she did, the same kind of pictures always showed up. One could see the

skin of the Others, even more than here at the beach. And then a lot of pictures

of an Other poking his skinstick into the opening of another Other.

Once Mona saw two Others do on the beach what she saw now in the box. First she had been fascinated, but soon grew apalled [sic] at their mechanical, jerky movements. That Other with his skinstick was so much more rude than Menno could ever be.

"Why are they doing this?" Mona asked. Menno looked over her shoulder and frowned. "I don't know. It doesn't look like fun. See how they look."

What is the appeal of cyberporn? Such a question might well be asked by one unused to this visual communication of - and vicarious participation in - sexual pleasure. An extension of more traditional forms of pornography and the repackaging of intercourse as a commodity, the Net, as a global arena, turns sex into a public and easily accessible display. Alienation from the natural, physical world thus becomes more widespread.

As the Net becomes a marketplace, it also inherits all the tricks of the marketing and advertising trades. Mona and Menno happen to encounter a particularly striking example of this, which again emphasizes the gap between nature and artifice, between reality and hyperreality:

-

Every time Mona hit a button, something new happened. "Hey, this is fun,"

Mona called out. Then it dawned on her that the [O]thers did not use this

thing only to look at pictures, but also for messages.

"What is credit card number?" she asked. "It says: Enter your security code and win a trip to the Carribean [sic]." "Great, that's where we already are." Menno laughed.

Aquatic beings on a beach in the Caribbean have little use for a free trip to the place they already are. The virtual lottery becomes another form of the marvelous discourse of the Net in which our ideas about the real and the unreal, the probable and the improbable are put on trial. The Net, indeed, invites humans to suspend their disbelief; the hyperreal invites us to forget the real.

Once again, the (virtual) Net comes to seem more and more like a (real) net in which it is possible to get caught; the bait, the potential of winning a prize, lures the unwary user who, in no time, will be hopelessly entangled in this cybernet. Leading its users through series of virtual open doors and windows, the Net hinders participation in real-world transactions. Bearing certain resemblances to Kiddo's cartoons, Lehmann's fiction suggests that the Net may be seen as a trap when viewed through the eyes of the cultural Other - this time it is not a neglected Other within the human race, but a non-human Other standing outside it.

At the same time, this story could be read in another way. It raises the issue of whether a critique of cyberculture from some of us in the "meatspace" of the unconnected Other world, arises out of our positions in the "culture wars", or out of what we have actually observed as the benefits and drawbacks of the Net. Cultural warriors may sometimes be too blind to recognize what they stand to gain from a culture that, to them, is equally Other. Like Mona and Menno, who abandon the gadget they have found, those who resist the Net because it is the signifier of the presence of the domineering Other, or because of what are perceived as its discursive "errors" in relating to life, may be throwing away a golden opportunity to access new knowledge and gain new understanding.[7]

| Concluding Remarks |

In this article, I have tried to show differing attitudes to hyperreality as reflected in an advertisement, some cartoons, and a short story about the Net. The NEToric of the advertisement shows up the myth-making surrounding the progress of business and the business of progress, twin challenges seen by the West as crucial in the globalization process. It is clear how easy it is to become caught in the net of such NEToric. The cartoons respond to such Techno-Utopianism critically and humorously, and deconstruct this discourse from an African perspective. In spite of the element of exaggeration typical of cartoons, they lead us to reflect seriously on obstacles to making the Net more relevant in Africa. The short fiction presents the condition of Otherness implied by Net culture in an unusual way, examining this cultural form through the eyes of an outsider - but at the same time showing non-humans taking advantage of the Net to validate their rather condescending view of human inferiority and unnaturalness. The aquatic beings do not want to be caught in/by the culture of the Other, but have they not also created obstacles to cross-cultural exchange and to their own needs for knowledge through their prejudices and their posture of resistance?

How can we remove barriers by creating more barriers? Viewing cyberculture merely as a Western cultural instrument of domination does not take us far. It only recuperates an argument that is, already, becoming a stereotyped reflex. The Net is a net also for the West. What is perhaps most essential at the present juncture in time is to see clearly: and that means continuing to interrogate the kinds of rhetoric which surround the Net's increasing intrusion into our daily lives.

Notes

[1] Through this semantic split, I allow for relativity in the idea of the "use" of the Net. Some uses of the Net could be perceived as "misuses", depending on the angle from which the medium is approached. For some, pornography, hate websites and criminal pursuits might constitute such "misuses".

[2] I use the term "Other(s)" (with a capital "O") throughout this essay to mean an entity that is imagined as being different from the Self in terms of ethnicity, race, religion, sexuality or even ideology. "Otherness" - the condition assigned to the Other - is sometimes imagined negatively, mainly because of the politics of the interpretation of difference, although natural evidence of difference can sometimes be identified. There is already a deluge of published material on Otherness or alterity, but perhaps the reader would like to consult Bruce Janz's "Alterity, Dialogue, and African philosophy" (1997), which contains an informative discussion on negative images of the Other. Also, Arob@se, vol.4, nos 1 & 2, fall 2000, carries interesting essays that examine the concepts of the Self and the Other from diverse scholarly perspectives, in addition to some that attempt to deconstruct this binary distinction.

[3] The term "Web" lends itself to wordplay in the same way as "Net"; see for example my article, "In the Web of His Sight: European Travel through Africa as a Virtual Encounter", which reflects on the Otherness of the African world in relation to Web narrative, imagining the Web as a trap spun by an ever-watchful "spy-der".

[4] For further information on the company, see https://www.sun.com/aboutsun/coinfo/index.html.

[5] "Kiddo" is the pseudonym adopted by the cartoonist. His/her actual identity is not provided for security reasons, but it should be noted that s/he is the major professional cartoonist with New People. Apart from providing cartoons as complements to essays and articles published in the magazine, Kiddo also has regular cartoon features entitled "KIKI AND KOKO" and "AFRICARTOONED". The latter, which adapts and reinvents the map of Africa as the head of a man in a fit of laughter (a cartooning of Africa, as the name of the column creatively suggests), regularly caricatures social and political situations in Africa, as well as the intervention of the global community in Africa's affairs. "KIKI AND KOKO", on the other hand, presents comic discourse situations in a matrimonial relationship, and is somewhat similar to the "Mr. & Mrs." cartoons in Vanguard, a Lagos-based newspaper. Both of Kiddo's cartoon features help to reinforce the discursive commitments of New People in relation to political and social crisis in Africa.

[6] Bill Readings (1994) attributes the anglocentric nature of the Net to "too many Star Trek reruns" seen by computer programmers rather than to "a conscious drive to global imperialism". Nevertheless, the fact that computer programmers, as he acknowledges, "apparently overlooked the existence of other languages than English while planning the system of communications for the 21st Century" suggests the same sense of being "caught in the Net" which is the subject of his essay. In this case, the net in which we are caught as users of the Net is interwoven with the language of the Center, the language that also globalizes culture. An extensive and stimulating discussion of this global authorization of English can be found in Pennycook (1994).

[7] See Sam Keen's (1986) elegant theorization of how resistance, pursued within the framework of the homo hostilis, amounts to an undoing of the position of the Self.

| © Cartoons reprinted with kind permission of New People. |

Bibliography

Arob@se. (2000) Special issue on "Ipseity and Alterity", vol.4, nos 1 & 2, fall. https://www.arobase.to/somm.html

Bastian, M.L. (1999) "Nationalism in a Virtual Space: Immigrant Nigerians on the Internet". West Africa Review, vol.1, no.1. https://www.westafricareview.com/war/vol1.1/bastian.html

Bernstein, B. (1975) Class, Codes and Control 3: Towards a Theory of Educational Transmissions. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bolter, J.D. (1996) "Electronic Technology and the Metaphor of the City". Telepolis, 01.01. https://www.heise.de/tp/english/special/sam/6029/1.html

Chilton, P. (1988) Orwellian Language and the Media. London: Pluto.

Dirks, T. (1996/2000) "Jaws (1975)". https://www.filmsite.org/jaws.html

Freyermuth, G. (1998) "The Net Is My Nest". Telepolis, 11.05. https://www.heise.de/tp/English/inhalt/co/2348/1.html

Horvath, J. (2000a) "Hidden Costs of Technology". Telepolis, 14.03. https://www.heise.de/tp/English/inhalt/CO/5901/1.html

Horvath, J. (2000b) "Delving into the Digital Divide". Telepolis, 17.07. https://www.heise.de/tp/English/inhalt/CO/8393/1.html

Isseroff, A. (1999) "Bad Connectivity May Be Better Than None". Telepolis Forum, 09.12. https://www.heise.de/tp/foren/go.shtml?read=1&msg=3&g=6551

Janz, B. (1997) "Alterity, Dialogue, and African Philosophy". Postcolonial African Philosophy: A Critical Reader. Ed. E.C. Eze. Oxford: Blackwell, pp.221-238.

Keen, S. (1986) Faces of the Enemy: Reflections of the Hostile Imagination. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Lehmann, V. (2001) "In the Net". Telepolis, 18.04. https://www.heise.de/tp/english/kunst/lit/7412/1.html

Mbogo, S. (2000) "Internet in Africa: WWW - The Winning War against Want?" New People, September-October 2000, pp.13-22.

Oguibe, O. (1996) "Forsaken Geographies: Cyberspace and the New World 'Other'". Paper delivered at the 5th International Cyberspace Conference, Madrid, June 1996. https://www.camwood.org/madrid.htm

Oguibe, O. (1999) "Connectivity, and the Fate of the Unconnected". Telepolis, 07.12. https://www.heise.de/tp/English/inhalt/CO/6551/1.html

Oha, O. (2000) "In the Web of his Sight: European Travel through Africa as a Virtual Encounter". Mots Pluriels, no.16, December 2000. https://www.arts.uwa.edu.au/MotsPluriels/MP1600oo.html

Olaniyan, T. (2000) "Cartooning in Nigeria: Paradigmatic Traditions". Ijele: Art eJournal of the African World, vol.1, no.1. https://www.ijele.com/ijele/vol1.1/olaniyan.html

Pennycook, A. (1994) The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language. London: Longman.

Porush, D. (1994) "The Rise of Cyborg Culture or The Bomb Was a Cyborg". Surfaces, vol.4. https://pum12.pum.umontreal.ca/revues/surfaces/vol4/porush.html

Readings, B. (1994) "Caught in the Net: Notes from the Electronic Underground". Surfaces, vol.4. https://pum12.pum.umontreal.ca/revues/surfaces/vol4/readings.html

Schuler, D. (1999) "The Cyber-Knave Conspiracy". Telepolis, 14.06. https://www.heise.de/tp/English/inhalt/CO/2944/1.html

Sun Microsystems, Inc. "About Sun" and "Company Information". https://www.sun.com/

Obododimma Oha is a lecturer in the Department

of English at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, but is currently on leave-of-absence

at the Université Gaston Berger de Saint-Louis, Sénégal. He has published papers

in various international journals and series including Mosaic, Africa,

Mattoid, American Drama, African Anthropology, Journal of Communication

and Language Arts, Context, African Study Monographs, and

Philosophy and Social Action. He has also contributed chapters to critical

anthologies. A poet and playwright, he teaches Stylistics and Discourse Analysis.

Some of his poetry can be found online at https://www.poetry.com/.

Obododimma Oha is a lecturer in the Department

of English at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, but is currently on leave-of-absence

at the Université Gaston Berger de Saint-Louis, Sénégal. He has published papers

in various international journals and series including Mosaic, Africa,

Mattoid, American Drama, African Anthropology, Journal of Communication

and Language Arts, Context, African Study Monographs, and

Philosophy and Social Action. He has also contributed chapters to critical

anthologies. A poet and playwright, he teaches Stylistics and Discourse Analysis.

Some of his poetry can be found online at https://www.poetry.com/.

Back to [the top of the page] [the contents of this issue of MOTS PLURIELS]