no 16 - December 2000.

https://www.arts.uwa.edu.au/MotsPluriels/MP16OOsm.html

© Sabine Marschall

and representing ordinary people's lives in

South African community mural art

Sabine Marschall

University of Durban-Westville

| THIS PAGE CONTAINS ILLUSTRATIONS. IT MAY TAKE A LITTLE WHILE TO OPEN. PLEASE BE PATIENT OR READ THE ARTICLE IN THE TEXT ONLY VERSION |

'Murals are anti-monuments - they do not celebrate individuals or heroes but the lived experience of ordinary people', observed Steven Sack in 1993 (Sack 1993), when urban murals were just beginning to mushroom in South Africa. The sudden interest in community mural art[1], which manifested itself first in large metropolitan areas and then spread to secondary urban centres and smaller towns throughout the country, is closely related to the changes in the political landscape and associated with major shifts in societal value systems. After decades of denigration and devaluation of Black African culture under Apartheid, the socio-political climate in the new South Africa following the First General Elections was ripe for Black empowerment, a strong affirmation of Black value-systems, heritage and cultural self-expression, allowing the previously silenced voices of the marginalised 'other' to come to the fore. Community mural art was to play an important part in this process.

Most obviously, community murals have the potential to benefit previously underpriviledged communities by beautifying and upgrading visually impoverished environments; by providing participating artists with much-needed, albeit temporary, employment; by granting them exposure; and by giving them an opportunity for further training through participation in preliminary workshops and the actual painting process. The teamwork manner of painting, the involvement of mostly Black participants[2], the generation of 'stories' and their detail from within the community, all contribute to making murals a site of reconciliation, cultural expression, self-representation and empowerment.

In this sense, the process of painting murals implements the South African government's White Paper on Art and Culture which demands access to and participation in the arts for all citizens, particularly the previously marginalised Black community, as well as encouraging cultural self-expression and agency. Lawrence Grossberg (1997:102), enquiring into the conditions and possibility of agency, points out that agency is not intrinsic to subjects but is rather defined by "the articulations of subject positions and identities into specific places and spaces - fields of activity. Agency is the empowerment enabled at particular sites, along particular vectors."[3] It is suggested that murals can be such sites and as such, as Steven Sack commented in 1993, "Murals can be signs of a new freedom" (Sack 1993).

This article will focus on murals that attempt to represent and validate the experience, history and cultural heritage of the previously marginalised African majority; in other words, affirm African culture and thereby contribute to reshaping Black African identity. It is in part due to the repetitiveness, banality and undramatic character of mural imagery that the South African art establishment has adopted a generally dismissive attitude towards murals.[4] Confronting the common lack of interest, this article aims to show that these images are a unique reflection of how the African community defines its own identity, aspirations and history. In its focus on ordinary people's lives and values, this study is lodged in the broader context of what is often referred to as 'popular history' or history 'from below' (Callinicos 1986), a field that has gained tremendous academic interest since the early 1980s.

Many community murals do not present us with dramatic narratives; they don't provide historical accounts in the Western sense of celebrating heroes, but, as Sack indicated, they focus on reflecting the lived experience of ordinary people. By far the most impressive and professionally painted murals of this genre are found at Umlazi Station (Illustration n°1) outside Durban[5]. Divided into rectangular panels, each one painted by one individual or a small group of artists, the walls are filled with realistically drawn large-scale images, set in shallow, but nevertheless illusionistic pictorial spaces. Viewed from a distance, the passers-by actually blend in with the life-size human figures in the paintings.

In accordance with the mural's specific site, the subject matter largely revolves around the theme of transport by train: people boarding and alighting from the train, Metrorail officials checking tickets, people waiting. The focal point, painted on the largest wall-section at the bottom of the stairs, is a humorous iconographic invention, the depiction of a train, 'humanised' by the addition of anthropomorphic features that transform the train front into a friendly, smiling face. Furthermore, topped by a pair of cattle horns and a traditional Zulu umancishana, objects used in ancestor worship, this gigantic icon of modern transportation technology has been 'secured' through the symbolical presence of the ancestors, suggesting their guidance and protection of the passengers.

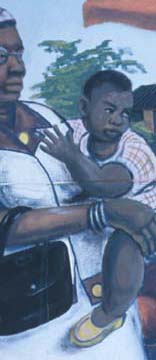

Most panels reflect aspects of local township life, images inspired directly by the local surroundings or drawn from the artists' memories and daily life experiences. A woman with child looks at fruit displayed on a vendor's table (Illustration n°2); men are drinking in a shebeen[6], while others work on a construction site; pupils in a classroom are eagerly focussing their attention on the teacher at the board; a woman is shown hoeing in the garden, while another walks along the street with her child on hand. The setting is furnished with recognizable icons of township life - the minibus taxi, the township houses, the Spaza shop[7] - and the well-known, highly visible landmark of the Umlazi water-tower. An enormous amount of carefully observed detail engages the passer-by and provides the basis for a positive identification with the images.[8]

This reflection of township life is not an accusatory, moralising representation of social ills and misery in the townships, but rather a straightforward, unpoliticised, matter-of-fact representation which is conceptualised and painted by Black artists and addressed to members of their own community. Much of the intensity of the images depends on the ordinariness of their actors, who are depicted as characters, well-known to the local community. The manner in which they dress and act, the accessories with which they surround themselves, the aspirations they appear to have - all these clues hint at the range of identities adopted by people who inhabit the contemporary African township situation.

Many of the images satirise common faults and weaknesses found within the community, intending to admonish individuals and providing desirable models of behaviour. The subtle moral message is frequently presented with a sense of humour that engages people, simultaneously entertaining and teaching them. Examples among the Umlazi Station murals include the old drunk who has fallen asleep and is being carried off in a wheelbarrow (Illustration n°3); or the man who is flirting with a young woman, alluringly dressed in a tight miniskirt and skimpy top, while a woman with two children is walking past, is perhaps an allusion to the man's own domestic situation.

Other scenes incorporate local stories and commemorate individuals from the community, who thus become part of the history of the place, the micro-history of the country. These images are encoded narratives, fully comprehensible only to the local community; they reconnect to the African tradition of oral history, becoming a recorder of local stories. A case in point is the image of an exterior domestic setting featuring a man who feeds beer to a goat, while others look on (Illustration n°4) The scene is based on the true story, well-known in the community, of an Umlazi resident who was thought to have turned his missing brother into a goat and henceforth fed it with beer because the brother used to be an alcoholic[9] (Zulu 2000). In a similar vein, a mural painted on the wall of a workers' facility in the Durban harbour area features images of the surrounding environment, enlivened by portraits of some of the labourers (Illustration n°5), who are thus publicly memorialised, providing the workers with a sense of pride and ownership.

When images of ordinary people's lives - such as the ubiquitous icon of the informal vendor - are found on walls within urban centres and formerly White suburbs, they can function as an acknowledgement of presence and laying claim to space. Controlling space has traditionally been a highly contested issue in South Africa, particularly in the cities and White suburbs. There the presence and movements of Black Africans was tolerated only within the boundaries of precise regulatory frameworks established by Whites. Murals in the cities reflect the new realities of a country in transformation. Murals contribute to reclaiming territory by acknowledging and thus legitimising the presence of people in areas where they were previously denied access or merely tolerated. The visual record of the mural thus becomes a public endorsement of what was previously perceived as a nuisance: the very presence of marginalised people and the flourishing of the informal economy as their source of subsistence in the city.

The mural on the perimeter wall of Medwood Gardens (Illustration n°6) in the Durban city centre[10] depicts a paradisiacal scene of lush vegetation with biblical allusions and hints at a well-known Zulu mythological story. The biblical references are clearly Africanised in their depiction of a Black primordial couple occupying this 'Garden of Eden' replete with its references to local South African scenery. This Christian narrative is pitched against traditional African mythology in the representation of the traditional Zulu story of the chameleon and the lizard.[11]

This was the first example of what became a series of murals based on traditional African stories painted by Durban-based Community Mural Projects. The mural group approached the City of Durban with a proposal, arguing the importance of recovering traditional African cultural heritage, folk-stories, belief-systems, mythology and other aspects of traditional African culture, perceived to be under acute threat or already lost through the pervasive influence of Westernisation and the social changes associated with an urban life-style. While the city accepted the proposal probably due primarily to its employment opportunities and urban upliftment potential, the time was certainly conducive to this line of argument. There was a strong awareness among intellectuals, politicians, community and cultural leaders of the need for validating and celebrating marginalised African cultural heritage: a need to focus on the stories that were never told before because they were not seen to be important.

As Thomas McEvilley (1993:11) has pointed out in his delineation of four phases of African cultural identity during the colonial/modernist period, the colonizer could dismiss the artistic expressions of the colonized merely by labelling them products of an inferior culture. In a drastic reversal of this precept during the post-Apartheid era in South Africa, products of artistic or cultural expression by Black Africans gained tremendously in importance and visibility.[12] In this respect it was significant that Community Mural Project's proposal envisaged the active participation of members of the community, both in the painting process and in the research of 'stories'.

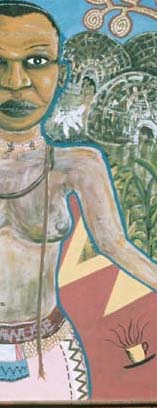

During the following months Community Mural Projects created the magnificently painted mural of the 'Seven-headed River Snake'[13], based on a locally sourced folk story[14] and the well-known and widely publicized Nomkhubulwana mural (Illustration n°7), both in Durban. The latter, completed only two days before the 1994 elections and towering over the busy crowds at the city node of Berea Station[15], represents Nomkhubulwana, the Zulu goddess associated with bringing of rain, thus enabling the crops to grow and providing the people with sustenance. The gigantic figure of the goddess is represented as a contemporary African woman, holding in her hand a madumbi, a common root vegetable and staple in many African people's diet. Her appearance is inspired by the very women frequenting the site and helps them relate to the goddess and so emphasise her closeness to the ordinary man and woman in the street.[16] Nomkhubulwana stretches out her hands in a gesture of embrace and reaching out, indicating her protection of and provision for her people who are depicted beneath: a diverse multitude shown in celebration and revelry. Individual images are directly inspired by the people who occupy this site: market women, fruit vendors, men playing cards, ordinary people passing by.

The Nomkhubulwana mural, on the one hand, celebrates traditional Zulu beliefs and honours and commemorates the once much-revered goddess. On the other, this emphatic, composite painting also expresses the spirit of reconciliation and hope that characterised this crucial time of the birth of a new society in the midst of great violence. Mythology plays a dual role here: at one level the painting's content draws on traditional Zulu beliefs with its meaning relying on a receptive context in which the viewer's insider knowledge is assumed; at another, it contributes to the creation of a new myth or a vision by visually representing the politically propagated concept of the 'rainbow nation' in the depiction of a multiracial crowd of people celebrating and "at peace with itself and the world." (Slessor 1995:98). A meaning that can be understood more inclusively by anyone conversant with the metaphors and new mythologies of contemporary South Africa.[17]

These murals can be seen as reconnecting with the African tradition of story-telling: the conveying of educational or moralising messages and preserving culturally specific beliefs and mythology through stories. The idea of translating oral tradition into a visual format soon inspired other artists and project leaders: for example, Malcolm Christian at Caversham Press in the Natal Midlands who invited 23 artists to create a print portfolio based on traditional African tales and legends (Anonymous 1996). Although the high degree of illiteracy or semi-literacy of the target audience would seem to make the recourse to visual language an ideal means of communication, it must be noted that the complete absence of a visual tradition of representation of such mythological stories appears to impede their accessibility and general comprehension.[18]

Closely related to representations of mythology and traditional beliefs are murals depicting episodes in African history with a focus on African 'heroes', or South African history from the perspective of Black Africans. The series of so-called Joko murals painted by Community Mural Projects in various cities around South Africa[19] (e.g. Rustenberg, Umtata, East London, Bloemfontein) exemplify this genre. They represent an aspect of the larger national project of 're-writing history', prioritised after the 1994 elections.

The 'Joko' mural in East London (Illustration n°8), for example, thematises the pivotal historical event of the Xhosa cattle-killing which virtually destroyed the Xhosa nation and opened up the land to British settlement during the 19th century. On the left, a group of elders are depicted sitting around the fire, smoking their pipes and, presumably 'telling stories', thus referring to the advert 'Joko story telling' below. The centre is occupied by a large frontal image of Nongqabuse, the young traditional healer who transmitted the fateful message to the Xhosa people, indicated on the right with cattle drowning in a massive river. The significance of this event for the expansion of British colonial influence is symbolically indicated in the backdrop which juxtaposes a traditional village and a typical colonial town replete with European style houses and a prominent church tower. The giant snake that winds around the tree in the traditional village has metamorphosized into a road passing through the colonial town.

Nothing in this mural hints at the fact that this episode of Xhosa history is highly contested terrain and that widely divergent accounts of the story exist: on the one hand the Apartheid version, which solely blames the Xhosa for their tragic fate, while on the other, the interpretation taught by activists of the liberation struggle which suggests a British ploy. But then the objective of this mural is not a critical investigation of an historical event and it is noteworthy that not even the local museum in East London, where this part of the region's history is completely omitted, has obviously been able to develop an 'official' version for display to the general public.[20]

Another aspect of the 'story-telling' murals is the supplementation of traditional folk-stories and history with newly invented narratives. The story of communication within the African community from ancient times to the present day, for example, is depicted in a Telkom-sponsored mural in the East London township of Mdantsane[21] (Illustration n°9). Following the common reading convention, from left to right, we are presented with an evolutionary path of technological development. Starting with a traditional rural village scene in which messages are carried across large distances no faster than a person can walk, it ends on the right with a modern urban office equipped with the latest electronic communications technology. The public Telkom phone, strategically placed in an urban setting near an accident scene, is shown to play a pivotal, potentially life-saving role. The mural artists have thus not only embedded the commercial message into a dramatic narrative to which everybody can relate, but they have created a larger story around it: an historical account dating back to time immemorial and revolving around an important aspect of their lives.

Another strategy employed to validate African cultural heritage is the equipment of murals with well-known icons and symbolic references to the African continent and African culture. Among such bold affirmations of Africa - intended not least to shift away from the European centre and relocate South Africa in Africa - are maps of the African continent; the choice of a colour scheme based on the colours of the African continent (red, green and black); slogans such as "Viva Africa"; references to traditional African art, such as masks and sculptures; the inclusion of traditional African musical instruments or other traditional objects such as weapons, pottery, or clothes. Less generally African and more specifically South African are the inclusion of the ANC colours (black, green and gold); the likeness of Nelson Mandela, former President and icon of the liberation struggle; references to symbols and metaphors of the new South Africa, in particular the national flag (Illustration n°10) and the rainbow, an allusion to the metaphor of the 'rainbow nation'; as well as references to ethnically specific imagery, such as decorative patterning based on Ndebele designs; human figures dressed in traditional Zulu attire; Zulu assegais[22] and traditional beer pots.

Then there are the ubiquitous images of the musician, which not only feature abundantly in mural art, but also in paintings on paper or canvas by contemporary Black artists. Although, without doubt, music plays a significant role in contemporary African township culture and many Black artists are themselves musicians, one suspects that the images of musicians and musical instruments are based more on stereotypes (e.g. ; the Black-American jazz musician as well-respected artist) than a reflection of reality and therefore rather serve a symbolic function. They acclaim African culture and artistic achievement, particularly through references to the saxophone and piano (pianists are rare amongst Black South African musicians) which, as opposed to drums, mbiras and other more traditionally African music instruments, have gained high respect within the Western-dominated world of music.

Two critical issues arise from here: The first concerns the presumed need for an 'Africanisation' of South African mural imagery. The question is whether a mural painted solely or predominantly by Black Africans addressed to a predominantly Black audience must have some kind of 'African character'; i.e., a recognisable, readily visible reference to Africa in order to be an authentic work of cultural self-expression. This is a highly debatable issue by no means specific to South African mural art, but rather underlying the entire field of contemporary African art production on the continent. As Vogel (1994) has shown, contemporary African art has always been polarised (consciously or subconsciously) between the two opposing ideologies of 'Africanness' (ultimately based on Senghor's concept of Negritude) and free artistic expression (i.e., the freedom of the African artist, like the Western artist, to chose subject matter and style without limitations).

There is also a significant distinction to be made between more generalised references to the African continent and African culture, as frequently found, for example, in Community Mural Project murals and more ethnically specific references (e.g., traditionally Zulu), as for example, in murals co-ordinated by Maphoyisa Magwaza or Stembiso Sibisi in townships around Durban. While general African references can still function as a broad point of identification across the racial spectrum, the ethnically specific iconography can be perceived as rather exclusive in comparison.[23] As Araeen (1994:3) has observed, "Indeed there has recently been a substantial critique of Eurocentricity, but it is often part of a search for alternative centricities." While the exclusive, ethnically specific references may be justified, depending on the context and the target audience, the relevance of Araeen's observation may be critical at other sites. This becomes particularly evident in KwaZulu Natal with its substantial Indian population, marginalised in the 'old' South Africa and, frequently feeling marginalised again in the 'new' South Africa. Surprisingly few of the public murals in the region acknowledge the Indian presence or celebrate Indian cultural heritage apart from token inclusions of Indians in representations of the 'rainbow nation'.[24]

The second critical issue concerns the danger of stereotyping; i.e., the perpetuation of existing stereotypes and the creation of new cliches. It appears that most representations of African people fall either into the category of 'township' type; i.e., Blacks dressed in Western clothes and surrounded by Western consumer goods and life-style, or the traditional rural type. The latter does not reflect contemporary reality, but a no-longer existing idealised past with representations of traditional African rural village environments untouched by Western influence. They reflect the same kind of melancholy and sentimentalism for the past that Vogel (1994) observed in countless paintings of urban painters throughout the African continent. It expresses the distance and remoteness that most of these artists seem to experience towards their own 'home village' or place of origin and a desire to record for the future a vanishing way of life (Vogel 1994:189). Recurrent images of Africans depicted in traditional bead and skin attire, equipped with traditional weapons and surrounded by objects of rural life furthermore suggest a kind of type-casting dangerously close to popular media images (from which they may even be derived) and related products of the tourist and heritage industry.

Apart from attire and surroundings, a closer look at the representation of Black Africans as agents, the kind of actions they perform and positions they occupy in society, reveals that the mural audience is hardly ever confronted with radically new models of identification. Even the new African elite - educated, prosperous, employed in responsible professional positions - is rarely depicted. One of the few exceptions is the office scene in the Telkom mural at Mdantsane, manned exclusively by Black Africans (although, in term of gender stereotypes, quite significantly both figures are male). In most murals, when showing people at work, Black Africans are likely to be pursuing menial tasks or labour occupations, albeit almost always in a dignified, sometimes heroicised manner: men are performing construction work and other types or labour, while women are occupied as teachers, taking care of children or sewing; both men and women are depicted vending or selling goods in small Spaza shops. The reason for this type of stereotypical imagery may be found partly in the presumed profile and expectations of the target audience. It is motivated by the desire not to highlight the extraordinary, but to celebrate and validate the ordinary, the mundane everyday life experience of the majority of common people.

Community mural production during the early transformation period, following the First General Elections in South Africa, is characterised by an enormous enthusiasm for the celebration and affirmation of African culture. One of the most powerful strategies employed to this end is the realistically painted representation of ordinary people : to celebrate their daily life experience, acknowledge their presence and provide them with models of identification. Other visual strategies include the representation of traditional African beliefs, the depiction of episodes from African history and the affirmation of Africa through well-known (often cliched) popular icons and symbols of Africa. Painted largely by Black artists, community murals can be considered a public forum for cultural self-expression, a unique reflection of a community's values and aspirations and as an indication as to how people see themselves.

In South Africa, the target audience of most murals is illiterate or semi-literate : people who have never been introduced to even the most basic principles of art appreciation, . It is not surprising therefore, that passers-by respond most strongly to (essentially banal) scenes of ordinary people's lives. Much more research is needed into the reception of murals, but it can be observed[25] that realistically painted murals, representing ordinary people , are infinitely more successful than those exploring more serious, weighty themes with profound messages, or those employing a more sophisticated visual language. Most Black Africans feel strongly attracted to imagery that relates to their own life-experience in a very literal and immediately comprehensible manner and with which they can personally identify.

This is a significant point because it means that serious or important messages can probably be conveyed more successfully when packaged into realistically painted scenes of ordinary people's lives. Mural artists or facilitators must be aware of the potential of such imagery to provide positive models of identification or teach moral lessons. On the other hand, as shown above, it is equally important for artists to be aware of the power of murals to create or perpetuate stereotypes. Given that murals are seen by large, anonymous crowds and that their imagery is likely to be received or consumed rather uncritically by the target audience, it is vital that mural artists and facilitators themselves are not without critical awareness.

Notes

[1] The term 'community mural art', in the context of this article, refers to contemporary urban wall-paintings created in a team work process by community artists with the involvement (to some degree) of the local community. All murals discussed here are painted on exterior walls, highly visible or accessible to the general public. For the purposes of this study, community murals are defined to be different from painted advertisement, 'fine art' murals (painted or designed by a single professional artist or graphic designer) and graffiti. Graffiti and community mural art are often lumped together and, on occasions, there is some overlap. However, by and large, graffiti differs from community murals in terms of visual appearance, motivation, and legality. [2] It is significant that most of these murals have been painted with a diverse group of participants, some of them established or academically trained artists, others informally trained or self-taught; occasionally, even artistically completely inexperienced members of the local community are being involved. This diversity and partial lack of experience accounts for the stylistic heterogeneity found in many murals and their overall somewhat 'naive' character. [3] Grossberg continues, "Such places are temporary points of belonging and identification, of orientation and activities, and as such they are always contextually defined. They define the forms of empowerment or agency which are available to particular groups as ways of going on and going out. Around such places, maps of subjectivity and identity, meaning and pleasure, desire and force, can be articulated." [4] For a more extensive discussion of the reasons for this disinterest, see Marschall 2000. [5] Painted in 1998, co-ordinated by Stembiso Sibisi. [6] Unlicensed informal bar and liquor store common in the townships. [7] Small, often informal, grocery shop in the townships. [8] That these murals are highly popular and provide successful models of identification has been established through interviews. See Marschall 1999. [9] According to Zulu (2000), this event took place around 1992/93. The man who was known for his knowledge of powerful traditional African medicine, or muti, claimed that he had turned his brother into a goat which he called Denis. He regularly fetched beer from the local shebeen to feed the goat and thus satisfy his alcoholic brother's needs. The community later killed the goat, believing that they would thus bring the brother back to life.The man insisted that the goat must be treated like a human being in terms of funeral rites and should be buried in the local cemetery. His request was, however, turned down by the local council. Eventually the community killed the man as well. [10] Painted by Community Mural Projects in 1993. [11] This story is about life and death. God sent the chameleon to earth to tell the people that they would henceforth be immortal. However, the chameleon was slow to get moving and the cunning lizard reached the people first, telling them that everyone would have to die one day (Zulu 2000). [12] On a more critical note it must be mentioned, however, that the sudden interest in Black artists and their works may, in some cases, have been precipitated by pressures towards constructing representative or politically correct 'rainbow nation' shows. [13] This mural has great visual appeal due to its harmonious colour scheme, a composition based on large-scale and lack of cluttering detail and a style of execution that appears more homogeneous than other works by Community Mural Projects. The actual narrative of the story is not represented, but the focus is entirely on the gigantic snake with its identifying characteristic of the seven heads, which occupies almost the entire wall space - ideally suited for the subject matter with its long, rectangular shape. Only on the extreme left and right are some glimpses of what is meant to indicate local rural scenery and traditional village life. [14] The story is about an evil snake that lives in the local river and preys on young girls as they come to the river to fetch water. Any attempt at killing the snake by cutting off its head results in another head springing up instantly. Only with combined effort does the community kill the snake in the end (Zulu 2000). [15] The mural was commissioned indirectly by the Bartel Arts Trust and painted by Community Mural Projects with the help of 15 artists drawn from various backgrounds including experienced muralists, students from the Natal Technikon and passers-by who simply asked to join the project (Slessor 1995). [16] This representation of the goddess as a modern woman, however, was not altogether successful. People experienced difficulties identifying the goddess, which eventually prompted the mural artists to 'label' the figure. See also Marschall 1999. [17] The Nomkhubulwana mural appears to be the first mural in the Durban area that visualizes the concept of the 'rainbow nation' and thus initiates a new discourse in public art productions of reconciliation and hope specific to the unique historical conditions of post-Apartheid South Africa. [18] See Marschall 1999. [19] Sponsored by Unifoods, the murals always contain a small advertisement message for Joko tea. The concept is based on the idea of tea-time as story telling time. [20] The same seems to apply to local history museums in other towns in the region, e.g., King Williamstown. [21] Painted in 1998, co-ordinated by Thabiso Khetsi. [22] Short spear introduced by King Shaka among his Zulu warriors. [23] It must be noted however, that the murals discussed are located at train stations in the townships frequented exclusively by Black Africans rather than a multi-racial crowd of passers-by in the city. [24] Perhaps most prominent among the few examples is the mural of Reconciliation in Ladysmith, co-ordinated by Lallitha Jawahirilal in 1995. [25] See Marschall 1999.

|

Illustration n°1 Umlazi Station. Umlazi. 1998. (Detail). Co-ordinator: Stembiso Sibisi. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°2 Umlazi Station, detail. Umlazi. 1998. (Detail). Co-ordinator: Stembiso Sibisi. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°3 Umlazi Station, detail. Umlazi. 1998. (Detail). Co-ordinator: Stembiso Sibisi. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°4 Umlazi Station, detail. Umlazi. 1998. (Detail). Co-ordinator: Stembiso Sibisi. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°5 Maydon Wharf, Durban. Portrait of a worker. 1998. (Detail). Co-ordinator: Leoni Hall. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°6 Medwood Gardens, Durban. 1993.Community Mural Projects. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°7 Nomkhubulwana mural. Durban. 1994. (Detail). Community Mural Projects. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°8 'Joko' mural. East London. 1996. (Detail). Community Mural Projects. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°9 'Telkom' mural. Mdantsane. 1998. (Detail). Co-ordintor: Thabiso Khetsi. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Illustration n°10 Beyond Awareness Campaign mural. tu. 1996. (Detail). Apt Artworks. © Do not reproduce without authorisation. |

Bibliography

Anonymous. Tales and Legends. Vuka SA, February 1996, pp.13-15.

Araeen, R. 'New Internationalism or the Multiculturalism of Global Bantustans', in Jean Fisher (ed.), Global Visions, Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts. Kala Press: London, 1994, pp.3-11.

Callinicos, L. 'The People's Past: Towards Transforming the Present'. Critical Arts, Vol 4, No.2, 1986; also published on the internet at https://www.und.ac.za/und/ccms/critarts/v4n2a2.htm

Grossberg, L. 'Identity and Cultural Studies: Is That All There Is?' in Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay (eds). Questions of Cultural Identity, London: Sage Publications, 1997.

Marschall, S. 'A Critical Investigation into the Impact of Community Mural Art', Transformation Vol 40,1999, pp.55-86.

Marschall, S. 'A Postcolonial Reading of Community of Mural Art in South Africa. Critical Arts: A Journal for Cultural and Media Studies 14 (2) September 2000..

McEvilley, T. 'Fusion: Hot or Cold?', in Fusion: West African Artists at the Venice Biennale, The Museum for African Art: New York, Prestel: Munich, 1993, pp.9-23.

Sack, S. 'Where walls are the fabric of freedom', Mail & Guardian 26/11-2/12, 1993.

Slessor, C. 'Delight', Architectural Review, March 1995, p.98/3.

Vogel, S. Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, Centre for African Art, New York and Prestel, Munich, 3rd edition, 1994.

Zulu, S. (Siphiwe). (Mural artist and Umlazi resident). Personal conversation, Durban, 2000.

Dr Sabine Marschall is a German art historian permanently residing in South Africa. After completing her PhD in

Art History at the University of Tübingen, she taught at Clemson University and Wofford College in South Carolina

(USA) and is currently lecturing at the University of Durban-Westville (mostly on 20th

century traditional African art). Recent publications focussed on 20th century South African architecture (Opportunities for Relevance,

co-authored with Brian Kearney, UNISA Press, 2000), on community mural art in South Africa and aspects

of South African art historiography.

Back to [the top of the page] [the contents of this issue of MOTS PLURIELS]