no 13 - April 2000.

https://www.arts.uwa.edu.au/MotsPluriels/MP1300kb.html

© Keith S.O. Beavon

Keith S.O. Beavon

University of Pretoria, South Africa

| THIS PAGE CONTAINS ILLUSTRATIONS. IT MAY TAKE A LITTLE WHILE TO OPEN. PLEASE BE PATIENT OR READ THE ARTICLE IN THE TEXT ONLY VERSION |

|

About four years ago a comment was made in a seminar paper at

the University of the Witwatersrand that the post-apartheid city in South

Africa would be distinguished from its previous character only in so far as

market forces would impose a "new apartheid" (Marcuse circa 1996). That

comment jelled with observations made over several years which seemed to

indicate that not only was the Central Business District (CBD) of Johannesburg

in decline; but by the late 1990s the surge of new shopping facilities, office

blocks, hotels, and entertainment facilities in the former 'whites-only'

northern suburbs of Johannesburg had increased the quality of life far beyond

what the white citizens of the city had previously enjoyed under the apartheid

regime. So massive has the growth been that what might be termed the new 'Johannesburg-in-the-North' may well be able to lay claim to some sort of 'world city' status, but it is also in danger of effectively becoming a neo-apartheid city (Beavon 1998b) and not part of what Bishop Tutu has styled the 'rainbow' nation. The intention here is to present some of the observations that have led to the impression just described and to conclude with a brief comment about some of the ironies of the present situation. It also seems appropriate that the present text should be set against a brief review of some of the research that has filled in the detail of the wider backdrop for any contemporary study of Johannesburg.

Established as a temporary mining camp in 1886, Johannesburg was the largest city in sub-Saharan Africa by 1894. From the outset it was a city with sharp formal race-divides yet by 1936 it was being hailed as a 'world city' (Beavon 1998a). Strangely, despite apartheid, it was still believed in 1986 that Johannesburg was the only 'world city' in Africa but ironically by 1995, because of the uncertainty of overcoming the legacy of the past, it had been removed from the list (Friedmann 1986, 1995). In part therefore one should set any discussion of Johannesburg as wholly within the context of the literature that defines 'world cities' (see Cohen 1981; Friedmann and Wolff 1982; King 1990; Sassen 1991; Hamnett 1994; Shachar 1994) and indeed within that of 'divided cities' (see Marcuse 1989, 1993; Beavon 1999). Yet within the confines of a short paper it seems appropriate to present the text as a vignette that must be seen against the contrasts illustrated in the literature where the chequered and blighted history of Johannesburg and its 'discarded' majority are chronicled. The best point of departure is the magisterial set of essays by van Onselen (1982a, 1982b) on the social and economic history of the Witwatersrand between 1886 and 1914. Next are publications where the trials, tribulations, and geographies of the poor and the sloughed-off areas of the city are high-lighted, commencing with the first forced removal in 1904 to what would be the nucleus of later Soweto (see Wentzel 1903; Greenlees 1912; Feetham 1934; Maud 1938; Kagan 1978; Kennedy 1984; Kallaway and Pearson 1986). Other themes cover the early racially-based slums (Parnell 1991, 1993), their persistence (Hellmann 1935, 1948; Koch 1983) and the growth and induced deterioration of the black freehold suburbs known as the Western Areas (Greenlees 1912; Lewsen 1953; Proctor 1979; Hart 1986; Hart and Pirie 1984), as well as details of the noisome 'hostels' (Pirie and da Silva 1986; Pirie 1988). The making of segregated Johannesburg before apartheid and the forced removals of the 1950s are well detailed (inter alia Davenport 1991; Lewsen 1953; Lodge 1981, 1983; Mather 1987; Stadler 1979; Morris 1980, 1981; Parnell 1988, 1992, 1993; van Tonder 1993a, 1993b). Several researchers have documented the changing racial geography of the city when black people began moving into proclaimed white-group areas particularly in the 1980s (de Coning et al., 1987; Fick et al., 1988; Pickard-Cambridge 1988; Dauskardt 1993; Morris 1994, 1997, 1999). Strange as it might seem, there is relatively little academic literature on the geography of affluence with the notable exception of studies of white socio-economic patterns in the 1960s and 1970s (Hart 1975; Hart and Browett 1976). More recently attempts have been made to spotlight the rapidity with which the affluence of the northern sector is being reinforced (Beavon 1997a, 1997b, 1998b; Beavon and Larsen 1998).

Doornfontein on the eastern side of the city was where the first 'Randlords' built their homes. By the early 1890s the rich had found a better location on the north-facing Witwatersrand Ridge, in what became known as Parktown. It not only served as a focus for a clutch of mansions but became the apex of the main wedge of what would later be known as the northern suburbs. Properties were in general much larger than elsewhere, were more expensive and lay beyond the then lines of public transport. It was the realm for the more comfortable classes with their own transport that granted them ready access to the burgeoning city centre with its fashionable shops, services, and 'watering-holes' when they needed them (Beavon 1996). Following the move off the gold standard, the city boomed in the second half of the 1930s. Investment also poured into Johannesburg's northern sector which with its flanking suburbs where the aspirant bourgeoisie chose to reside, bulged ever northwards (Figure 1) although residential density remained essentially unchanged from that of the early 1930s (Figure 2) Increased ownership of private automobiles after the Second World War helped to extend the northward expansion (Figure 1). Even so, the large central business district located just north of the mining-land continued to be the single most important meeting point for people of all races although its opulence was reserved for whites only. Yet as early as 1959 there were signs, missed by most and notably by the city authorities, that the small emergent suburban nodes could change the business pattern of the city (Lauf 1959).

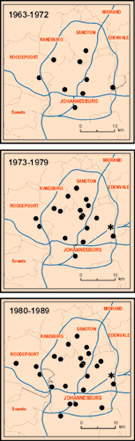

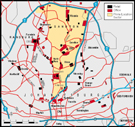

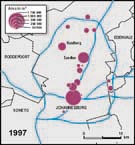

Competition for tertiary activities grew between 1959 and 1967 when, for political reasons, the State created two new municipalities, Sandton and Randburg, in what at the time was the periphery of Johannesburg's northern areas (van der Spuy 1967; Carruthers 1980). In order to secure their own tax base the new towns aggressively competed for business with Johannesburg. In the case of Sandton, the core of their CBD by 1973 was a 30 000 m2 shopping mall known as Sandton City (Figure 3). By the late 1970s another three malls of more than 10 000 m2 had opened in Sandton's suburbs. Others were built in the neighbouring municipalities of Bedfordview and Randburg, and in three of Johannesburg's northern suburbs (Figure 4) (Sapoa 1993). The first of the mega-malls, Eastgate (Figure 4) opened in 1978. With 90 000 m2 of shopping and service businesses, it was three times as large as the Sandton City Mall until then the biggest in the metropolitan area. By 1978 one third of all white shoppers were making their purchases in the suburban centres alone. Whereas 70 per cent of all shopping in the Johannesburg municipal area was still made by white people, they accounted for only 52 per cent of the total sales in the CBD (Oosthuizen 1983; Mandy 1984). The mid-1980s saw the loss of four of the largest and most prestigious department stores in the country from the Johannesburg CBD. Three of the firms re-established premier stores in the new malls (Mandy 1984), attracting a growing number of dependent high-order speciality stores to the same locations. Thus by the end of the 1980s the basic pattern of retail decentralization, with a focus on large malls, was already well established (Figure 4). What followed in the 1990s was a virtual shopping explosion that substantially reinforced the earlier pattern (cf. Figures 4 and 5). As early as 1993 the South African Property Owners' Association (Sapoa) had recorded that there was already 941 500 m2 of retailing outside the Johannesburg CBD, situated in only 29 malls that were at least 10 000 m2 in size. By 1995 an additional eight malls, exceeding 10 000 m2 each, had been opened and total space in the 37 nodes had increased by 24.3 per cent to 1 169 827 m2, whereas the Johannesburg CBD still contained only a nominal 700 000 m2 of retailing (Ampros 1994a, 1994b; Beavon 1998). As additions were made to existing older malls their retail area reached 1 263 902 m2 by late 1999 thereby exceeding the current retail space of the CBD by a factor of 1.63. One must note in passing that there are numerous small shopping centres and suburban malls that have less than 10 000 m2 of lettable space and that are not included in the 1.26 million m2 just mentioned (Sapoa 1993, 1995, 1997, 1999a; Beavon 1998). Most of the suburban retailing lies in the broad central wedge of the northern suburbs (Figure 6). As shown on (Figure 5), there is relatively little in the way of major malls south of the Johannesburg CBD. The most glaring 'open space' is to the southwest, the area that contains Soweto and that, even now, has only one shopping facility of more than 10 000 m2. Little wonder therefore that so many Sowetans continue to shop in the down-graded Johannesburg CBD that is no longer of any importance to the white shoppers of the northern suburbs. Even if it still offered high-order retailing, its ability to attract white shoppers from the north would be low (Figure 7). For them to reach the Johannesburg CBD they would have to travel past malls that already stock the full range of items that are normally found in the centre of any first-world city. In terms of normal shopping behaviour, the malls en route to the CBD would simply 'intercept' the shoppers.

Suburban office space has followed a similar pattern of location to that of the malls (cf. Figures 8 and 5). By 1982 there was about 350 000 m2 of office space in the northern suburbs, equal to 9 per cent of the total office space in Johannesburg as a whole. Significantly between 1981 and 1984 some 431 000 m2 of office space was under construction in the suburbs vis-a-vis only 205 000 m2 in the CBD (Mandy 1984). By the beginning of 1993 A- and B-grade office space in the CBD (Figures 9 and 10) amounted to approximately 1.6 million m2, but there was already some 2.4 million m2 of similar grades of office space in the suburban nodes. The 'late expansion' of CBD office space, prompted by the prospects of a democracy heralded by political events in 1990-91, was completed between 1993 and late 1997, pushing the amount of high-grade office stock in the CBD to 1 732 100 m2. Yet by late 1999 suburban office space of grades A and B had risen to 3 339 589 m2 as the demand for large amounts of space by major corporations leaving the Johannesburg CBD continued (Sapoa 1999b) (Figure 11). Between the beginning of 1993 and late 1999 the gap between the total amount of A- and B-grade office space in the CBD and in the suburbs had widened by 110 per cent, from nominally 758 000 m2 to 1.6 million m2. The result is that for every square metre of high-grade office space that has been added to the Johannesburg CBD since 1993 approximately 7.5 m2 of equivalent or better quality space has been provided elsewhere in the suburbs. Furthermore the demand for office space outside of the CBD has exceeded that for space within it by a ratio of at least 8.6 to 1. By mid 1998 it was being claimed by property analysts and brokers that the vacancies in the CBD would take 10 years to fill at current take-up rates whereas there was only a 4 month supply in the thriving northern suburban nodes. The amount of A- and B-grade office space in the main Sandton business node (Figure 12) has increased by 87 per cent between 1990 and the end of 1999, and is equal to 63 per cent of what had been in the CBD of Johannesburg as recently as 1990 (Sapoa 1999b). Sandton in general is steadily attracting major corporations to what was its former independent municipal area and the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, the premier exchange of Africa and the top emerging market exchange in the world, will move to new premises in Sandton towards the end of 2000. There it will join most of the 75 foreign banks that are established in South Africa as well as the headquarter units of many, if not most, of the major financial business houses (Maher 1994; Beavon 1999b). The rapid increase in the amount of office space in the northern suburbs has brought with it a concomitant increase in the number of white-collar workers. With office nodes closely allied to the pattern of malls, the volumes of weekday shoppers at lunch-time in the northern malls is substantial. For similar reasons there is now also a vast choice of fashionable restaurants, 'watering holes', fast-food outlets, places of entertainment and 5-star international hotels. Yet although most white residents of the north no longer visit the old CBD area, it remains the single most accessible point of the Witwatersrand and as such, the north is probably now more insular and inward facing than it ever has been. The possibility that it is the first genuine "edge city" (Garreau 1991) in South Africa is currently being researched (Larsen 1999).

As the incidence of crime in the suburbs increased dramatically in the 1990s so did the cost of securing property, thereby causing a shift towards smaller more easily protected premises, particularly for first-time white buyers. Consequently large numbers of cluster units, various forms of townhouses and other types of 'gash' (good address small house) accommodation have mushroomed relative to the proverbial 'large house with large grounds and a pool' typical of the older areas in the northern suburbs. As the new 'lock-and-go' style of living has become more popular, the residential densities in small pockets of the north are now higher than ever before, although by northern hemisphere standards, or by the standards in black townships, they remain ridiculously low. Even, so the additional population in no way represents an increase comparable to that experienced in the sphere of retailing, service business and office space. Although the only barrier to entering any residential area is price, in reality that alone creates a form of de facto apartheid. Of course there are a significant number of well-positioned and wealthy black people now living in many of the expensive northern suburbs. Yet the overwhelming majority of black people remain literally and figuratively on the margins, largely as a consequence of the cards dealt them in the apartheid years when they were growing up, seeking an education and searching for a good job. So, although there are no longer any racial barriers to where one might live, the northern 'wedge' (Figure 6) and the suburbs adjacent to its western side remain overwhelmingly white. The anomaly is the poverty-stricken Alexandra township that has been a black ghetto (Figure 13) almost since its founding in 1912 (Nauright 1998). Unfortunately there is no published analysis based on a definitive data set of property transactions for the last decade to give a quantitative picture of what has been described here. The 1996 census, in respect of enumeration districts is not available in the public domain and can only be obtained by purchasing it from the State for a substantial sum of money! On the basis of a small non-random sample of 9 000 transactions in greater Johannesburg between 1993 and 1996, a commercial research firm (Prinsloo 1997) has established that the percentage of houses purchased by black people in the former whites-only suburbs in the southwest (nearest to Soweto) ranged from 63 per cent to a mere 3 per cent closer to the former 'white' city. In the northern suburbs sales to black buyers have amounted to between only one and two per cent of all sales made. In simple terms the 'picture' that emerges is one of 'business as usual' in a still 'divided city' with no real signs of genuine intermingling of races in the former whites-only suburbs being visible by 1999. Although it cannot be fully considered here, for those familiar with the relevant literature, it should be apparent that there are distinct parallels between the socio-economic characteristics of Johannesburg's northern suburbs and the situation of the middle-class in major south-east Asian cities (see Dick and Rimmer 1998). There is also sufficient evidence to suggest that northern Johannesburg might rate well on the scale of criteria for what has been termed the proto-global city (Hall 1997), particularly if allowance is made for its regional setting and role in sub-Saharan Africa or even for the continent as a whole.

It is important to bear in mind that the theme of the present paper is not about the decline of the Johannesburg CBD and its inner-residential areas. Nonetheless the decay in the city centre and in the adjacent high-rise residential areas, accompanied by what is described as crime and grime, has strengthened the push factors towards the northern suburbs. Certainly a case could be made that what has occurred is white flight prompted by white fright. The reasons for the phenomena just mentioned lie beyond the scope of the present paper but have been presented and analyzed elsewhere (see Dauskardt 1993; Beavon 1998b, 1999a; Morris 1999). The focus at this point in the paper is on how the reinforcement of wealth and opportunity in the north has been perceived and what future reaction might be. Careful monitoring of press reports over a ten-year period has shown that there has been more concern about the decline of the Johannesburg CBD, and the increase in physical and social blight in the downtown and its residential zones, than with the accumulation of wealth and power in the north. Yet when it was announced late in 1998 that the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (Figure 14) was to move from the centre of Johannesburg to Sandton it did evoke a reaction in the press, on talk-radio and amongst political leaders that gave a hint of what might be pent-up emotion to what has been described earlier in this paper. "Bulls and Bears Join the Chicken Run" was a headline in the largest Sunday national newspaper (Sunday Times, 1/11/1998) with the sub-head reading "Plan by JSE [Johannesburg Stock Exchange] to Seek Greener Pastures in Sandton will Deal a Hefty Blow to City Centre, say Critics". Private anger directed at what was happening in the north was demonstrated in a letter published in at least two newspapers (The Star 13/11/1998; Sunday Times 15/11/1998). In it the writer claimed that the decline of the Johannesburg CBD was a smoke-screen:

Furthermore, within days there were reports in the press that the Premier of the Province and its head of Development Planning and Local Government had agreed to impose a ban on further office and other business developments outside the Johannesburg CBD. The plan was subsequently denied (Sunday Times 20/12/1998) but Johannesburg's Saturday Star stated in a leading article (on 2/1/1999) that "there is also merit in the government's argument that the office developments in the north have prejudiced black workers, who find it more difficult to get to work from their homes in places like Soweto". Whether the reactions cited above are the only reactions, and whether they are genuinely only concerned about the decline and depletion of the central area of 'old' Johannesburg, remain to be seen. It should be noted however, that already the so-named Eastern Metropolitan Local Council, the municipal sub-structure that encloses the wealthiest part of the northern suburbs, has raised local property taxes (rates) by up to 300 per cent. The rate-payers also contribute to a redistributive levy that sees 51 per cent of the rates paid going to the less-advantaged areas of other municipal sub-structures. Notwithstanding an initial counter-reaction in the form of an almost two-year boycott of their dues by those who pay the rates, the payments from that group are now back to regularly high levels. In the light of the above it therefore appears timely to ask whether there will be further reaction against the laagered 'rich', or indeed from them. At present there is only sufficient evidence to support speculation. It might be an appropriate moment for those who are interested in the situation to conduct some genuine research in order to hypothesize what lies ahead for the as yet disparate members of the 'rainbow nation' in the northern parts of metropolitan Johannesburg.

Readers with wide experience of cities might well say that the 'white flight' from the CBD to the north is merely yet another example where those with enough money (usually whites) withdraw from the crime and grime of the downtown and ensconce themselves in exclusive suburbs. True enough; and in one sense Johannesburg (and indeed other South African cities) now resembles more closely those cities of the world where central-city decline and decay has been matched by the new suburbanization that creates greater divisions between rich and poor, and between whites and other races. In the case of Johannesburg the change is doubly significant. The goal of the new democratic government, after all, is to produce a "new" South Africa, a "rainbow nation" which will not be cleaved along lines of race. Yet it appears from what is set out in this paper that in Johannesburg one is witnessing the rapid consolidation of a new system of racial separation, this time modelled on the 'accepted' experience of other societies. One must wonder whether that alone makes what is happening in northern Johannesburg acceptable or whether the neo-apartheid aspects warrant greater concern and further investigation. |

Figure 1. The northward expansion of Johannesburg and its metropolitan area 1900-1992 (modified from Whitlow and Brooker 1995). © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 2. Distribution of the white population in 1931 (adapted from City Engineer 1970). © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 3. The office tower with its shopping-mall podium together known as Sandton City circa 1978 (viewed from the west). © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 4. The distribution of shopping malls of at least 10 000m2 in size, 1963-1989. The position of Eastgate, the first of the super-malls, is indicated with an asterisk/star. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 5. The distribution of shopping malls (at least 10 000m2 in size) that opened and grew between 1990-1997. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 6. The central northern 'wedge' of metropolitan Johannesburg which contains the most sought-after sites for new malls and office developments (modified from Moross and Partners 1995). © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 7. One of the consequences of long-term vacant space in older office buildings has been the growing incidence of demolitions such as this one (1995) in the vicinity of the City Hall now the seat of the Provincial Legislature. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 8. The distribution of nucleations of top-grade office space in and beyond the Johannesburg CBD, 1997. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 9. The skyline of the Johannesburg CBD in 1997 viewed from the east. The tallest building is the 50-storey tower of the Carlton Centre. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 10. The office-blocks of the CBD (left) merge into the high-rise residential skyline (centre and right) of the inner-residential zones in the suburbs of Hillbrow and Berea (viewed from the east). © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 11. Low-rise office parks invading the suburbs in the vicinity of Hyde Park (see Figure 6). © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 12. The skyline of central Sandton in 1997. Sandton City (see Figure 3) which stood out like a sore thumb in 1980 is now barely noticeable as the tall grey building on the right-hand side of the picture (viewed from the west). © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 13. The 'urbanscape' of Alexandra township seen from the air (circa 1988). The large lozenge-shaped buildings in the sea of houses and shacks are the single-sex hostels for migrant workers. © Do not reproduce without authorisation.  Figure 14. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) adjacent to the all-glass 'Diamond Building', containing the head office of Anglo-American Properties, as seen in 1995. Both are located on the western edge of the Johannesburg CBD and abut the derelict central power station with its small squatter settlement. © Do not reproduce without authorisation. |

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the University of Pretoria for funding the research and Mesdames Booysen and Geringer of the Cartographic Unit of the Department of Geography and Geoinformatics for assistance in preparing the maps and illustrations for publication. Dr Jim Campbell of the Afro-American Studies programme at Brown University in the USA and Professor Belinda Bozzoli of the Department of Sociology at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg offered words of caution and advice on the manuscript for which I am most grateful

Bibliography

Ampros. "Vacancy survey of completed office buildings" unpublished report. Anglo-American Property Services, Johannesburg, 1994.

Ampros. "Report(s) on the letting market(s) of (the) Commercial District(s)" in Ampros Research. (July to November). Johannesburg: Anglo American Property Services, 1994b.

Beavon, K.S.O. "Johannesburg 1886-1896: the unfolding geography of the first ten years' Arena. 3 (9). 1996, pp.12-16.

Beavon, K.S.O. "Johannesburg: A City and Metropolitan Area in Transformation" in C. Rakodi (ed.). The Urban Challenge in Africa: Growth and Management of its Large Cities. United Nations University, Tokyo, 1997a, pp.150-91.

Beavon, K.S.O. "Critical Factors in the Long Decline of the Johannesburg CBD: a Warning for Suburban Shopping Centres" invited paper presented at the Property Executive Programme Conference entitled The Challenge -- Get the Basics Right, held under the auspices of the South African Property Owners Association, Johannesburg, 1997b.

Beavon, K.S.O. "'Johannesburg': Getting to Grips with Globalization from an Abnormal Base" in Fu-chen Lo and Yue-man Yeung (ed.). Globalization and the World of Large Cities. United Nations University, Tokyo, 1998a, pp.352-388.

Beavon, K.S.O. "Nearer my Mall to Thee: The Decline of the Johannesburg Central Business District and the Emergence of the Neo-Apartheid City" unpublished seminar paper No. 442 presented to the Institute for Advanced Social Research, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1998b.

Beavon, K.S.O. "Johannesburg: From Segregated Mining City to Post-Apartheid Metropolis, 1886-2000" book-length manuscript being revised for publishers, 1999a.

Beavon, K.S.O. "Johannesburg, 112 ans de division: de la ségrégation à la ville post-apartheid'in J-B Onana (ed.)> Questions Urbaines en Afrique du Sud. L'Harmattan, Paris, 1999b, pp. 9-86.

Beavon, K.S.O. and Larsen, P. "Capital productivity" Productivity SA. 24 (1). 1998, pp.27-30.

Carruthers, E.J. "The Growth of Local Self-Government in the Peri-Urban Areas North of Johannesburg, 1939-1969" unpublished M.A. dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria, 1980.

City Engineer: " Greater Johannesburg Area Population Report F.P. 17" Forward Planning Branch, City Engineers' Department, Johannesburg City Council, Johannesburg, 1970.

Cohen, R.B. "The New International Division of Labor: Multinational Corporations and Urban Hierarchy" in M. Dear and A.J. Scott (eds.). Urbanization and Urban Planning in Capitalist Society. Methuen, New York, 1981, pp. 287-315.

Dauskardt, R.P.A. "Reconstructing South African cities: contemporary strategies and processes in the urban core" GeoJournal. 30. 1993, pp.9-20.

Davenport, T.R.H. "Historical Background of the Apartheid City to 1948" in M. Swilling, R. Humphries and K. Shubane (eds.). Apartheid City in Transition. Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1991, pp. 1-18.

de Coning, C., Fick, J. and Olivier, N. "Residential settlement patterns: a pilot study of socio-political perceptions in grey areas of Johannesburg" South Africa International. 17. 1987, pp.121-37.

Dick, H.W. and Rimmer, P.J. "Beyond the Third World City: the new urban geography of South-east Asia" Urban Studies. 35. 1998, pp.2303-2321.

Feetham, R. (Chairman) Report of the Transvaal Asiatic Land Tenure Act Commission. Parts I and II. (U.G. 7/1934), Government Printer, Pretoria, 1935.

Fick, J., de Coning, C. and Olivier, N. "Ethnicity and residential patterning in a divided society: a case study of Mayfair" , South Africa International. 19. Johannesburg, 1988, pp.1-27.

Friedmann, J. "The world-city hypothesis" Development and Change. 17. 1986, pp.69-84.

Friedmann, J. "Where we Stand: A Decade of World City Research" in P.L. Knox and P.J. Taylor (eds.). World Cities in a World-System. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995, pp. 21-47.

Friedmann, J. and Wolff, G. "World city formation: an agenda for research and action" International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 6. 1982, pp.309-43.

Garreau, J. Edge City: Life on the New Frontier. Anchor Books, Doubleday, New York, 1991.

Greenlees, M.R. (Chairman) Report of the Transvaal Leasehold Townships Commission. (U.G. 34/1912). Government Printer, Cape Town, 1912.

Hall, P. "Modelling the post-industrial city" Futures. 29. 1997, pp.311-322.

Hamnett, C. "Social polarisation in global cities: theory and evidence" Urban Studies. 31. 1994, pp.401-24.

Hart, D.M. and Pirie, G.H. "The sight and soul of Sophiatown" Geographical Review. 74. 1984, pp.38-47.

Hart, T. The Factorial Ecology of Johannesburg. Occasional Paper No. 5. Urban and Regional Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1975.

Hart, T. and Browett, J.G. A Multi-variate Spatial Analysis of the Socio-Economic Structure of Johannesburg, 1970. Occasional Paper No. 13. Urban and Regional Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1976.

Hellmann, E. "Native life in a Johannesburg slum yard" Africa. 3. 1935, pp.34-62.

Hellmann, E. Rooiyard, a Sociological Survey of an Urban Native Slumyard. Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1948.

Kagan, N. "African Settlements in the Johannesburg Area 1803-1923" unpublished M.A. dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1978.

Kallaway, P. and Pearson, P. Johannesburg: Images and Continuities -- A History of Working Class Life through Pictures 1885-1935. Ravan, Johannesburg, 1986.

Kennedy, B. A Tale of Two Mining Cities: Johannesburg and Broken Hill 1885-1925. Ad. Donker, Johannesburg, 1984.

King, R. Global Cities: Post Imperialism and the Internationalisation of London. London: Routledge, 1990.

Koch, E. "'Without visible means of subsistence': slumyard culture in Johannesburg 1918-1940" in B. Bozzoli (ed.). Town and Countryside in the Transvaal. Ravan, Johannesburg, 1983, pp. 151-75.

Lauf, G.B. "Opening Address" in E.W.N. Mallows (ed.) Summer School. South African Institute of Town Planners, Johannesburg, 1959, pp. 1-5.

Larsen, P. "The Rise and Status of Sandton: the New CBD of Johannesburg" unpublished M.A. proposal. Department of Geography, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 1999.

Lewsen, J. "The city council and the 'Western Areas' removal scheme" in South African Institute of Race Relations, The "Western Areas" Removal Scheme: Facts and Viewpoints Presented at a Conference Convened by the S.A. Institute of Race Relations at the University of the Witwatersrand 22nd August 1953. South African Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg, 1953, pp.3-5 .

Lodge, T. "The destruction of Sophiatown" Journal of Modern African Studies. 19. 1981, pp.107-32.

Lodge, T. Black Politics in South Africa since 1945. Ravan, Johannesburg, 1983.

Maher, M.G.K. (compiler) The JSE Handbook. Flesch Financial Publications, Johannesburg, 1994.

Mandy, N. A City Divided: Johannesburg and Soweto. Macmillan, Johannesburg, 1984.

Marcuse, P. "'Dual city': a muddy metaphor for a quartered city" International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 13. 1989, pp.697-708l

Marcuse, P. "What's so new about divided cities?" International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 17. 1993, pp.355-365.

Marcuse, P. Race, Space, and Class: The Unique and the Global in South Africa. Occasional Paper Series. Department of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, (n.d., circa 1996).

Mather, C. "Residential segregation and Johannesburg's 'Locations in the Sky'" South African Geographical Journal. 69. 1987, pp.119-25.

Maud, J.P.R. City Government: the Johannesburg Experiment. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1938.

Moross and Partners. "Johannesburg Nodal Development Study" unpublished report prepared for the Johannesburg City Council , Moross & Partners Inc., Johannesburg, 1995.

Morris, A. "The desegregation of Hillbrow, Johannesburg, 1978-82" Urban Studies. 31. 1994, pp.821-834.

Morris, A. "Physical decline in an inner-city neighbourhood: a case study of Hillbrow, Johannesburg" Urban Forum. 8 (2). 1997, pp.153-175.

Morris, A. Bleakness and Light: Inner-City Transition in Hillbrow, Johannesburg. Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg, 1999.

Morris, P. Soweto. Urban Foundation, Johannesburg, 1980.

Morris, P. A History of Black Housing in South Africa. South Africa Foundation, Johannesburg, 1981.

Nauright, J. "'The Mecca of Native Scum' and 'a running sore of evil': White Johannesburg and the Alexandra Township removal debate, 1935-1945" Kleio. 30. 1998, pp.64-88.

Oosthuizen, A. "The metropolitan retail scene with special reference to the Witwatersrand" unpublished paper delivered to the Rand Afrikaans University Retail Seminar, March 1983.

Parnell, S.M. "Racial segregation in Johannesburg: the Slums Act, 1934-1939" South African Geographical Journal. 70. 1988a, pp.112-126.

Parnell, S.M. "Slums, segregation and poor whites in Johannesburg, 1920-1934" in R. Morrell (ed.). White but Poor: Essays on the History of Poor Whites in Southern Africa 1880-1940. University of South Africa, Pretoria, 1992a, pp. 115-29.

Parnell, S.M. "State intervention in housing provision in the 1980s" in D.M. Smith (ed.). The Apartheid City and Beyond: Urbanization and Social Change in South Africa. Routledge, London, 1992b, pp.53-64.

Parnell, S.M. Johannesburg Slums and Racial Segregation in South African Cities, 1910-1937. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1993.

Pickard-Cambridge, C. The Greying of Johannesburg: Residential Desegregation in the Johannesburg Area. South African Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg, 1988.

Pirie, G.H. "Housing essential service workers in Johannesburg: locational constraint and conflict" Urban Geography. 9. 1988, pp.568-83.

Pirie, G.H. and da Silva, M. "Hostels for African migrants in greater Johannesburg" GeoJournal. 12. 1986, pp.173-82.

Prinsloo, D. "Black advancement into former 'Whites only' suburbs" Urban Studies. Published by Urban Development Studies, Johannesburg, 2 (1), 1997, pp.1-4.

Proctor, A. "Class struggle, segregation and the city: a history of Sophiatown 1905-1940" in B. Bozzoli (ed.). Labour, Townships and Protest. Ravan, Johannesburg, 1979, pp. 49-89.

Sapoa Shopping Centre Directory 1993. South African Property Owners' Association, Sandton, 1993.

Sapoa Shopping Centre Directory 1995. South African Property Owners' Association, Sandton, 1995.

Sapoa Shopping Centre Directory 1997. South African Property Owners' Association, Sandton, 1997.

Sapoa Shopping Centre Directory 1999. South African Property Owners' Association, Sandton, 1999a.

Sapoa Office Vacancy Survey: September 1999. South African Property Owners' Association, Sandton, 1999b.

Sassen, S. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1991.

Saturday Star. Weekly newspaper, Johannesburg.

Shachar, A. "Randstad Holland: a 'World City'?" Urban Studies. 31. 1994, pp.381-400.

Stadler, A.W. "Birds in the cornfield: squatter movements in Johannesburg, 1944-1947" Journal of Southern African Studies. 6. 1979, pp.93-123.

Sunday Times. Weekly newspaper, Johannesburg.

The Star. Daily newspaper, Johannesburg.

van der Spuy, J.J.S. (Chairman) Ondersoek na die Skepping van 'n Munisipaliteit vir die Bryanston / Sandown / Noordoos-Johannesburg Gebied en die Verandering van die Munisipale Grense van Bedfordview, Edenvale, Johannesburg, Randburg en Roodepoort. Transvaal Provincial Administration, Johannesburg, 1967.

van Onselen, C. "Studies in the Social and Economic History of the Witwatersrand 1886-1914" New Babylon. Ravan, Johannesburg, 1982a, Vol.1.

van Onselen, C. "Studies in the Social and Economic History of the Witwatersrand 1886-1914" New Nineveh, Ravan, Johannesburg, 1982b, Vol.2.

van Tonder, D. "Boycotts, unrest, and the Western Areas Removal Scheme, 1949-1952" Journal of Urban History. 20. 1993a, pp.19-53.

van Tonder, D. "'First Win the War, then Clear the Slums': The Genesis of the Western Areas Removal Scheme, 1940-1949" in P. Bonner, P. Delius, and D. Posel (eds.). Apartheid's Genesis 1935-1962. Ravan and Wits University Press, Johannesburg, 1993b, pp. 316-340.

Wentzel, C.A. (Chairman) Report of the Johannesburg Insanitary Area Improvement Scheme Commission, Transvaal Government, Johannesburg, 1903.

Whitlow, R. and Brooker, C. "The historical context of urban hydrology in Johannesburg. Part I: Johannesburg, 1900-1990" Journal of the South African Institute of Civil Engineering. 27 (3). 1995, pp.7-12.

Professor Keith S.O. Beavon is Professor of Geography and Head of the Department of Geography and Geoinformatics at the University of Pretoria. His

main research interests are in Urban geography, currently the historical and contemporary urban geography of Johannesburg, 1886-2000.

Recent publications comprise:

"Johannesburg, 112 ans de division: de la ségrégation à la ville post-apartheid" in Jean-Baptiste Onana (ed.) Questions Urbaines en Afrique du Sud. Paris: L'Harmattan, 1999, pp. 9-86;

"'Johannesburg': coming to grips with globalization from an abnormal base" in Fu-chen Lo and Yue-man Yeung (eds) Globalization and the World of Large Cities. Tokyo: United Nations University, 1998, pp.352-388;

"Johannesburg: a city and metropolitan area in transformation" in C. Rakodi (ed.) The Urban Challenge in Africa: Growth and Management of its Large Cities. Tokyo: United Nations University, 1997, pp.150-192.

| Paper presented at the African Studies Association of Australasia & the Pacific 22nd Annual & International Conference (Perth, 1999) New African Perspectives: Africa, Australasia, & the Wider World at the end of the twentieth century |

Back to [the top of the page] [the contents of this issue of MOTS PLURIELS]