No 19. October 2001.

https://www.arts.uwa.edu.au/MotsPluriels/MP1901mh.html

© Michael Heim

Michael Heim

Art Center College of Design, Pasadena

| The Arrival of the Avatar |

| avatar (pronounced AV-uh-tar): A word adopted

by computer users to denote the digital manifestation that humans take

on when entering virtual worlds. The word is Sanskrit for the […] incarnation

a god takes on Earth. Vishnu, the Hindu god responsible for maintaining

the existence of the universe, has 10 important avatars, including Krishna,

the philosopher king, and Varaha, the boar who rescues the planet after

it is inundated by the oceans. The 10th avatar of Vishnu, Kalki, will

arrive in the future to destroy the world with fire and begin a new

age of purity on the planet. - Glossary of Internet Terms at PCNS, a division of MoveWare, https://www.pcns.net/internetterms.html |

When it arrives, the avatar's presence demolishes the Internet as we have known it. What we now know as "the web," the hyperlinked library of two-dimensional audio, video, images and texts, is absorbed into an interactive, self-presentational avatar space with three, four, or more dimensions. To appear, the avatar requires at least a simulated three-dimensional space where its graphic body can navigate and establish social co-presence with other avatars. Such avatar space has been struggling to be born during the past decade in such online multi-user virtual communities as ActiveWorlds, Blaxxun Community, and Adobe Atmosphere. The avatar has not yet blossomed but has germinated quietly in small seed beds of hobbyists and avant-garde artists. Hovering on the verge, avatars are powerful presences that could transform the Net into true cyberspace, into an online multi-user virtual reality (OMVR). As broadband web access spreads, the 3D web brings us closer to the arrival of the avatar.

Avatar space can swallow the older media of linked documents, images, streaming audio and video. OMVR cyberspace first appeared in the early 1980s when the term "cyberspace" indicated a cybernetic depth dimension, but the 1990s mainstream web obliterated cybernetic depth with a flat two-dimensional mosaic (Netscape) of texts and images which may have ignited popular fancy and commercial ambition, but which pushed aside the search for depth. If the avatar does ever indeed arrive, that incarnation of real-time human presence will scorch the assumptions of the two-dimensional asynchronous universe, where the book culture still lingers with its single-author paradigm. The avatar transforms private, desk-bound egos into intersubjective, world-building artists.

The avatar challenges the power assumptions that the web today enforces. Today's society bases its power on the computer screen, which is a kind of grid. Screen terrain is a grid surface. The grid displays picture elements or pixels that simulate analog realities like desktops, folders, and other iconic references. Staring at the grid is the human subject, often experienced as an encapsulated, isolated ego defined by the narrow rationality made famous by the philosopher René Descartes, whose cogito ergo sum describes a solitary consciousness that looks outwards on everything as a separate "outside" reality. How does the world look to the detached Cartesian ego? Since this ego feels itself to be a monad - an independent and self-sufficient unit - the surrounding world appears at a distance through a control grid that allows the ego to monitor incoming events with precision and calculation. The grid overlays every experience like a computer monitor that allows the eye to filter every digitized event by placing it on coordinate axes of width, height, and depth (X, Y, Z axes). The Cartesian coordinate grid traps every possible movement across the terrain of measured awareness. Measurement and precision enable the eye to maintain a feeling of control, of monitoring the world from a distance. Precision and control come by renouncing the role of participant. The Cartesian ego is not fundamentally a participant in the world it observes. By fixating on the screen that separates it from everything other than itself, the ego becomes a victim trapped by its own need for watching and surveillance. The ego falls into the trap of the power grid, as the grid reflects the ego's own isolated craving for control.

The avatar first arises in the most primitive form as a moving cursor on the grid screen when that screen becomes networked with other screens. The cursor on the user's screen opens a mouse hole in the unified power grid. Through the moving cursor we see revealed the mind of a human subject who is navigating information. The appearance of a tiny cursor movement in networked environments - as the cursor movement becomes visible on all client computers on the network - causes a unique flicker in the power grid of computer systems that control vast amounts of information. The mouse moves, the cursor crosses the screen, and with that movement the human subject, who would otherwise be concealed by the screens, stands forth. Though tiny in relation to the larger terrain of the computer screen, the cursor points to a mouse that roars. The mouse bespeaks an alternate notion of computer space where the information grid is shot through with human subjectivity. The cursor mouse becomes the seed of the avatar, the potential of cyberspace to mix information with intersubjectivity and with real-time communication.

Through networking, the cursor begins to reveal the activity of the human subject behind the power grid. The cursor is the first glimmer of the avatar that peeks through the entrapping grid. Several stages precede the avatar morphology, from the smiley face in emails and the shared programs with real-time white boards, to the nickname handle in a chat room. As it eventually moves onto the screen and inside the virtual world, the graphic avatar comes to value participation above power, and self-transformation above control. The avatar is the fully conscious manifestation of the networked cursor. Stepping out into the computer grid, the avatar attains moments of self-realization as the user chooses shape, clothing, and modulated voices with which to enhance the moving avatar. The avatar is not a separate icon of human presence, not merely a graphic to track a real-time user. The avatar exists in a context or world. The world is a graphical place where avatars move, act, and interact with one another. The avatar exists with other avatars, or at least with the anticipation of potentially interacting with other avatars. Through their co-presence, avatars achieve an experience of immersion, of being more deeply inside the graphical world. The depth dimension of cybernetic space opens with the advent of the avatar.

In avatar worlds, the distant Cartesian ego acknowledges itself to be inside a space full of spontaneous real-time encounters. The encounter space peels back the wall of control that protects the grid of power. As the cursor grows into avatar, cyberspace ceases to be flat information waiting to be accessed. By its entry, the avatar seeks recognition by others who have also momentarily escaped the grid. Avatar space adds multiple subjects to cyberspace. These subjects constitute a neighborhood of virtual identities through intersubjectivity and mutual recognition. The recognition is not face-to-face recognition. The avatar screens out primary properties in favor of a chosen fantasy identity. Avatar space liberates the fanciful imaginative identities of real egos. As they shed Cartesian trappings, these egos receive the invitation to recreate themselves and be transformed through their fantasy.

| Avatar Communities are Not Broadcast Audiences |

|

An avatar is a being of some sort that is a graphical

representation of you, the user in, for example, a multi-user world.

In such a multi-user world typically there are many avatars. Each

avatar is the virtual representation of the human controlling that

avatar. The avatar does not have to be human and may be any graphical

nature of any type. |

The avatar may sometimes look like Mr. Potato Head, but the avatar is no couch potato. The avatar space reforms the passive role of broadcast audiences. The passive broadcast audience was a product of very specific historical developments. The modern audience did not become a group of listeners by gathering around storytellers or oral poets. Television and radio are systems for propagating information and opinion to mass audiences that can be polled statistically and that remain faceless (hence the term "mass" audience). The audience became a social class ("silent majority") and an object of propaganda, as content was propagated by marketing agencies and/or politicians. The mass audience grew in the twentieth century but originally sprang from a nineteenth-century notion of audiences. The television and radio audience was an historical child of a reformed operatic theater. The formation of the audience came as a result of changes in theatrical architecture initiated by the opera-drama composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883).

The Wagnerian "theater of the future" influenced theater design throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.[1] Before Wagner, the operatic theater was a loosely organized, open song hall where audiences enjoyed socializing, snacking, and applauding their favorite singers. When encouraged by applause, divas would launch forth to sing another popular tune, drinking song, or romantic song that might have nothing to do with the drama on stage. Compared with operatic theater after Wagner, the concert hall was chaotic - what we might today call participatory or even interactive. Wagner changed the nature of audience involvement when in the late 1870s he built a single-purpose opera hall in Bayreuth, Germany, which was soon emulated in subsequent theater architecture throughout the world. Wagner was concerned with dramatic musical narrative, with music that was tightly wedded to narrative action; he opposed the unfocused grand operatic spectacles popular in Europe.

To shape a new kind of attentive audience, Wagner built a new kind of theater. In collaboration with the architect Gottfried Semper, Wagner worked out architectural plans for a Festival Playhouse from 1855 to 1867. This famous Bayreuth Festival Playhouse would exert a profound influence on theater style, which then shifted from the horseshoe-shaped, multi-tiered, balconied opera house to the Roman-style odeum or amphitheater with a second proscenium and a sunken orchestral pit, which allowed the audience greater intimacy with the drama onstage. The laws of perspective created an illusion of great depth, with a space or "mystic gulf" separating the "real world" of the spectators from the "imaginary world" of the stage. The gulf and the perspective created a focused audience who were then drawn in as silent, staring witnesses to a psychically moving event. This new focused concentration became a vital part of the Bayreuth Theater and later influenced the aesthetics of opera houses like the Burg Theater in Vienna, the opera house in Dresden, and theaters in Prague, Altenburg, Stettin and the Royal Albert Hall in England. Its outlines were seen in countless other theaters from New York to Odessa, and the amphitheater in the Prince Regent's Theater in Munich.

The audience members thus became focused individuals who did not interact with one another socially, but who lived for a time only in imagination influenced by stirring music, dramatic staging, and poetic language. This dreamy audience eventually became the passive consumer audience, hypnotized by propaganda and commercial culture. The Wagnerian audience was the forerunner of the impersonal mass audience that inherited television, radio, and cinema.

The avatar breaks the spell of passive video. Avatars socialize with avatars in real time. Users create fantasy identities that are projected and actively engaged by other avatars. The user both accepts and asserts identity as the scene changes with every movement of the avatar's point of view. The memory function of virtual worlds - "building" in ActiveWorlds, furnishing an "apartment" in Blaxxun's "CyberTown," or creating your own "Portal" in Adobe Atmosphere - gives self-created identity a cumulative shape. Unlike the broadcast audience, the avatar is both artist and audience. The challenge for virtual worlds designers is how to evoke the artistic engagement of users at a level appropriate for their skills and their capacity for freedom.

One aspect of the emerging avatar appears in the widespread phenomenon of Instant Messaging (IM). Messaging belongs to the multi-tasking skills of the next generation. Youth today are typically performing several tasks simultaneously on the personal computer: searching the web, burning a CD-ROM, watching TV, talking on the phone, and chatting with a friend using Instant Messaging. The typical multi-tasking routine shows complex psychological juggling where a traditional audience mentality coexists with the pre-Wagnerian audience mentality that insists on socializing. The interactive component varies in the mixture, sometimes taking the foreground, sometimes receding to quiet whispers. The Cartesian ego behind the screen dissolves into chat with friends while watching TV while exploring new music available on the web. The experience is not linear like narrative drama, nor does it exclude narrative drama. The avatar defines the overarching model of the experience because the avatar inhabits shared worlds built on multiple identities and constructed of thoroughly fungible digital content. By breaking the spell of broadcasting, the avatar recovers human freedom, revives spontaneity in the face of linear programming, and seeks to inhabit the telepresent world in a creative way.

| CyberForum@ArtCenter |

Experiments with non-linear - that is, not narrative- or broadcast-based - fantasy chat began at the Art Center College of Design (Pasadena, California) in January 2000. The CyberForum@ArtCenter started its experimental series in hopes of discovering and then amplifying the inherent principles of avatar chat in virtual worlds. Art Center students designed virtual worlds that were visually tailored for each Forum event, and theory students supported the events by hosting authors and artists who had written about virtual worlds or who had created avatars as art forms. For each event, participants arrived online from several continents to participate. From its inception, CyberForum sought to channel the events into short time spans of an hour each and then to extend and preserve those events in log files and discussion boards. To date, more than twenty events have been logged by the Forum.[2] Instead of the unfocused, informal chat worlds used by hobbyists and gamers, the Forum adopted the compressed event format of academic lectures but placed these lectures inside fantasy avatar environments that were each fashioned to fit their particular topic. A spirit of relaxed fun was injected into the serious topics addressed by the authors or artists who were central to each event.

A typical example of the relaxed fantasy lecture was the "Plankton Float" which took place on two occasions during the Summer 2000 series of CyberForum. The general theme of the Summer series was "The Avatar and the Global Brain." The theme centered on current theories that describe the Internet as an evolutionary mechanism for gradually shaping a global consciousness. Two Forum speakers for the series came from the group Principia Cybernetica. The Principia Cybernetica Program (PCP),[3] based in Brussels and Los Alamos (New Mexico), frames theories loosely described as "global brain" theories. These see networked information systems as driven by an internal evolution that is self-correcting and self-generating (autopoetic). Especially hyperlinked systems, such as the Internet, are considered self-evolving because of a continual self-selection: frequently used hyperlinks become more embedded and come to replace less useful links which gradually disappear. In this way, the system as a whole is "self-aware" and increases in intelligence, according to PCP. If we imagine the Internet as a global nervous system, the brain of advanced society grows collectively smarter. Such automatic evolution leads some PCP theorists to make analogies that sometimes cast individual humans as passive victims. If individuals are off the grid for one reason or another, PCP theory demotes them to an awkward position. One phrase used in a PCP paper describes humans reluctant or unable to get wired to the Internet as "plankton" for consumption by the evolutionary behemoth, suggesting that reluctant individuals with their private aberrant thoughts are irrelevant. It was this image of helpless plankton that inspired design students to create avatars that resembled plankton and to devise a "ritual" for the Forum that would enact the human plight so mercilessly described by the PCP group.

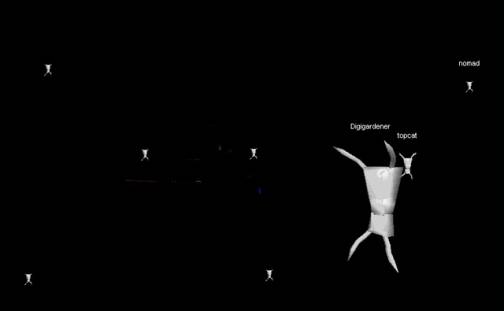

The Summer Forum invited Francis Heylighen and Cliff Joslyn, co-founders of PCP, to speak at separate events. Both events involved the "Plankton Float" ritual. For the Plankton Float, participants donned avatars shaped like awkward plankton and descended into a dark ocean-like pocket of cyberspace to perform ritual movements that exercised the limited functionality of the plankton avatars while they floated amidst a few animated bubbles. With their stubby arms and legs, the plankton could hardly do more than float vertically or swim horizontally. The plankton-like avatars appeared passive and helpless in the belly of cyberspace while they bobbed up and down or moved slowly past one another, remaining within a small enough area to be visible as an ensemble. The Float ritual required the participants to navigate cyberspace vertically in a smooth, varied line within eyesight of one another, while at the same time chatting and discussing the issues of PCP theory. Once the bobbing started and the plankton achieved smooth synchronization, the group began talking about the dehumanization implied by the plankton metaphor of evolutionary survival. The speakers from PCP realized some unfortunate aspects of their metaphor and promised never to forget the Plankton Float (see figure 1 below).

The Forum demonstrated the value of participatory avatar rituals for engaging users and bringing them to a realization through playful avatar activity. The immersive engagement with avatars opens an inroad into the deeper recesses of the psyche and creates powerful memories through visual imprinting.

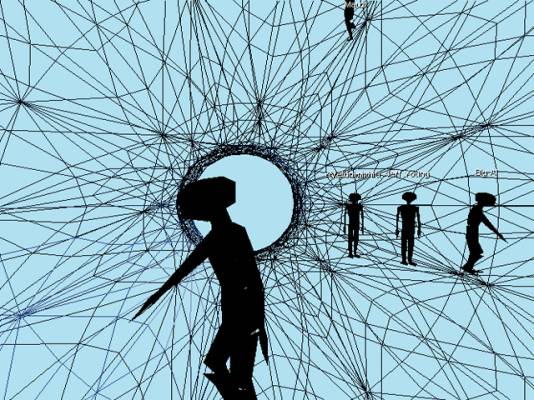

Another example of an avatar ritual was the "Avatrapment" event. This fantasy

ritual occurred during the VLearn 2000 / Avatars 2000 conference held in ActiveWorlds

on October 14-15, 2000. Avatrapment featured a cage-like wire frame that trapped

avatars in an infinitely unfolding lattice. The Forum topic on that occasion

pointed to the danger of being trapped in avatar worlds that do not connect

to real-world structures. The ritual placed forty participating avatars into

the wire-frame cage. As a participant headed for an exit, the cage suddenly

popped up in a new form to surround the avatar. The cage design used warps

and visibility limits to achieve its effects. Avatars bounced back and forth,

creating a constantly shifting kaleidoscopic image (see figure 2 below).

Each networked computer monitor showed different moment-by-moment perspectives on the scene. The ritual provided a group activity that was both fun to do and keyed to the concept. Again, the topic and the ritual together elicited amused discussion among the participants, and the idea of entrapment harmonized with the visual experience.

| Conclusion: Information or Communication? |

For decades, information systems have been evolving largely along the lines set by the logicians and philosophers whose intellectual assumptions made computers possible. Seventeenth-century rationalists like Leibniz, who built the proto-computer, established a system of binary information that, they hoped, would unify empirical scientific efforts. Knowledge could then advance more rapidly, they theorized, on a transnational level with less wasted replication. Scientific findings could be coordinated through written correspondence and through the establishment of scientific societies and official academies of science. In some important ways, the legacy of pan-rationalists like Leibniz still endures in what we today call the Internet. Inasmuch as we take the Internet to be a vast repository of information for globalizing human knowledge, we continue the trajectory of the rationalist philosophers who laid the foundations of computing at the beginning of the Modern era.[4]

Recent developments in networked computing raise the possibility of a contrary trajectory. The contrary trajectory moves toward computing as a communication platform as much as an information system. And from the perspective of the counter-trajectory, we face several questions. Could the flourishing of MUDs, MOOs, chat rooms, and Instant Messaging be a distinctly human interruption of the silent library that potentially houses all human knowledge? Might speeding information be stopped in its tracks by a distinct alternative to the systematic concept of the Internet? Is not a telepresent space taking shape that defies the hierarchy of information cataloging? And rather than conceiving of all human communication as material for the global Internet, what would happen if we took seriously the emerging communication space as a contrary movement to the collection, storing, and sorting of human symbols? Could the two distinct trajectories merge on a higher level that would enrich both?

To sharpen the contrast, we have looked at the most radical and distinctive entity in the eruption of communicative space-time: the avatar. The graphic avatar belongs, of course, to virtual worlds, but virtual worlds appear, as worlds, only when humans don avatars to enter and navigate them. Together in-world, graphic avatars recognize other avatars and even build common projects using virtual models.

The avatar arrives just in time to offset the tendency of the Net to become a giant database, a warehouse of third-person information that is compressed, stored, and exploited. Our sciences are uploading genetic information from millions of years of human, animal, and plant evolution, constructing powerful biological data banks. The rich genetic information in these biological data banks is being used by researchers to remake the natural world. The uploading process of this technology, which is the compression of nature into data blocks, has been made possible by twenty-first-century computers and telecommunications. Computers are increasingly used to decipher, manage, and organize the vast store of genetic information that is the raw resource of an emerging biotech economy. How do we upload our human identity? Does our identity - that of biological beings - "fit" into the database? Are we about to become another compressed data block? What part of us escapes data entry?

The answer proposed here is that there is a part of us that has an ally in the avatar. Through avatars, humans emerge not in Luddite opposition to technology but in new aesthetic phenomena. The avatar is a cybernetic art work that appears inside the network systems and that affirms the human psyche in the belly of the technological behemoth. Through avatar worlds, the network becomes a platform for individual expression and for social interaction, a communication system where human presence is affirmed by first-person chat and by fantastical gestures. The spontaneous structuring of shared time - synchronous real time - functions as cybernetic liberation. The avatar breaks through the everyday power grid required by an increasingly computerized society. The avatar arrives through computer creativity, through sociality inside the cybernetic system itself.

Notes

[1] The account of Wagner's influence is indebted to a book by my friend Frederic Spotts, Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994, pp.38ff). None of my speculative conclusions should be attributed to Spotts.

[2] Log files with screen shots from the CyberForum are archived online at: https://cyberforum.artcenter.edu/.

[3] For more information about PCP, visit: https://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/.

[4] More comments about Leibniz's seminal contribution to computing can be found in the author's books The Metaphysics of Virtual Reality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993) and Electric Language (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999 [1987]). The author's translation of Heidegger's book on Leibniz (The Metaphysical Foundations of Logic, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984) also contains a "Translator's Introduction" which highlights the rationalist trajectory. The "Translator's Introduction" can be found under "Books" on the author's website at: https://www.mheim.com/. See also a full-length study by Martin Davis, The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2000).

Michael Heim develops concepts

for cyberspace and virtual reality. Wired Magazine described

Heim's work as "a warm-hearted, cool-headed meditation on computer technology."

Library Journal said, "This is Marshall McLuhan with a solid grounding

in philosophy." Heim's writings have been translated into Chinese, Japanese,

Korean, Hungarian, Polish, and German. His books include Electric Language

(Yale University Press, 1987, 2nd ed. 1999), The Metaphysics

of Virtual Reality (Oxford University Press, 1993), and Virtual Realism

(Oxford University Press, 1998). He was the 1997 Visiting Research Professor

in the Visual Construction of Reality at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark;

in 1999 he was Guest Professor at the University of Graz, Austria; in 2001

he was Digital Cultures Fellow at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

He currently teaches Virtual Worlds Theory and Virtual Worlds Design at the

Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, where in 1995 he received

the Great Teacher Award from the graduating class in Computer Graphics and

New Media.

Michael Heim develops concepts

for cyberspace and virtual reality. Wired Magazine described

Heim's work as "a warm-hearted, cool-headed meditation on computer technology."

Library Journal said, "This is Marshall McLuhan with a solid grounding

in philosophy." Heim's writings have been translated into Chinese, Japanese,

Korean, Hungarian, Polish, and German. His books include Electric Language

(Yale University Press, 1987, 2nd ed. 1999), The Metaphysics

of Virtual Reality (Oxford University Press, 1993), and Virtual Realism

(Oxford University Press, 1998). He was the 1997 Visiting Research Professor

in the Visual Construction of Reality at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark;

in 1999 he was Guest Professor at the University of Graz, Austria; in 2001

he was Digital Cultures Fellow at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

He currently teaches Virtual Worlds Theory and Virtual Worlds Design at the

Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, where in 1995 he received

the Great Teacher Award from the graduating class in Computer Graphics and

New Media.Back to [the top of the page] [the contents of this issue of MOTS PLURIELS]